Writing politics during the pandemic

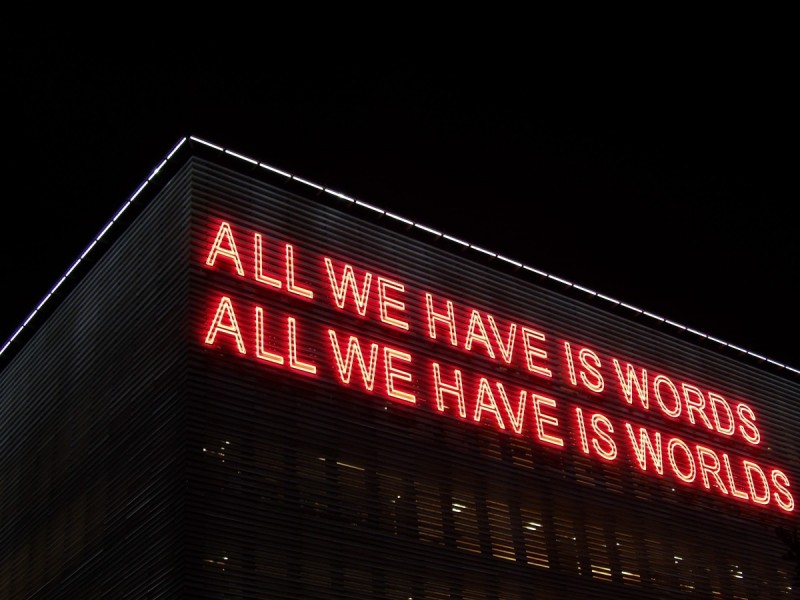

Neon installation by British multimedia artist Tim Etchells, displayed on the side of the Onassis Cultural Centre in Athens, Greece from November 7, 2016 to July 31, 2017. Photo from Unsplash.

Throughout the late winter and spring in Ontario, frustration with Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government grew as COVID-19 cases surged. Experts, advocates, and observers had long been calling for action on employer-paid sick days, effective lockdowns, targeted vaccination programs, long-term care facility reform, and plenty more. Then, on Friday, April 16, the premier announced scattershot measures throughout the province, including arbitrary police carding powers and the shut-down of playgrounds. At the same time, he ignored most of the measures public health experts had been urging for months.

The press conference was a turning point. Or perhaps a boiling point. We’d all had enough. Condemnations of the premier and his plan were swift, devastating, and widespread.

I watched the press conference, taking notes and sharing in the collective catharsis of panning the premier on social media, watching timelines go from PG-13 to R in real time. I replied to texts and direct messages, each of which went something along the lines of “Has he lost what was left of his mind?”

For a moment, the pain of distance and atomization of the past year or so—already a phenomenon part and parcel of a liberal experience that undermines community—aggravated beyond reason by the pandemic, seemed to abate. I was slated to write about the federal budget the following Monday, but wrote to my editor at The Washington Post and asked if I could write about Ford instead; that is, if I could write a column calling for him to resign. He wrote back. I could indeed. And so I stayed up late that night and did.

When something happens in the political world—an issue makes it onto the public agenda or a law or policy is passed—it is typically because people have worked to organize and grow it from idea to action. From same sex marriage to Indigenous reconciliation to childcare to pharmacare to cannabis legalization and so on, struggles for rights and justice are collective undertakings in which groups of advocates, experts, workers, and day-to-day individuals organize and press for change.

Often, politicians and members of the media get attention and credit for outcomes, but it is the labour and commitment of those who organize that turns struggles into outcomes, and the bulk of the credit belongs to them. The writer and political class provides air support, complementary to whatever material and other labour support they might add, but typically this is an adjunct undertaking. The core work happens on the ground, in the workplace, in small offices and meeting spaces, and on the street.

Throughout the pandemic, we have been further removed from one another, making organizing and advocacy work more challenging for many. Forced to stay home or limit contact with others, lest one spreads the virus, there has been a premium on digital activity—especially as we spend more time on social media. Influencing and holding decision makers to account now includes virtual space to an extent we have yet to witness or make sense of before now. While social media spaces are not representative of the population, they are filled with journalists and politicians and advocates and organizers, making them critical spaces for shaping discourse and outcomes whose central work happens offline. The two-space reality of social and political life was in place before the pandemic and has only become more widespread and entrenched since the coronavirus began to spread. We need to make sense of it.

My piece was posted on Sunday, April 18, two days after Ford’s disastrous press conference. I was on my couch playing PlayStation, connected to my friends the way I stay connected these days, through a gaming party. We were playing World War Z, a game of zombie waves; all the better to distract us from the horrors of the pandemic. I posted the piece between missions and my next pint, then watched the share count soar. I went back to the game. Later, checking back, I saw the piece had topped the Post’s most-read list. My e-mail inbox, social media mentions, and texts filled up.

Writing past midnight on Friday, I figured I had something. The piece didn’t take long to write. Maybe 45 minutes, most of which was spent getting the right links to support a rundown of Ford’s disastrous time in office and fact-checking evolving details. It didn’t take long to write because I knew what I wanted to say. Following the experts and the advocates and countless residents of Ontario, it had long been obvious that Ford was in over his head. Their anger and frustration confirmed my own. It wasn’t just me. This government was as bad as it seemed.

The job of a politics writer who gets paid to give their opinion includes the work of sharing what you believe to be true, setting the agenda and advocating for what you believe is good or right. It also includes mirroring back to people that which they believe to be true or good or right, provided you agree with them, concentrating their hopes and frustrations and desires and rage. Writing, in that way, is a collective act contrary to the old, typically macho, myth of the solitary writer.

Even deep into the pandemic, sundered from one another, we are sharing spaces and exchanging information, experiencing this moment together, even if we are physically apart. There is still an opportunity to approximate the solidarity of the streets—though not replace it—by writing and sharing in collective anger, frustration, and demands for better. Our virtual communities cannot replace our physical communities any more than writing columns can replace organizing. But those virtual communities are places of action that shape opinions, preferences, and outcomes as they bring us together in an imperfect yet often welcoming, even comforting, way.

In the post-pandemic world, with all the current talk of the future of work and media and organizing, we should remember that a functioning democratic system must include physical, direct action in the streets, reading groups meeting at coffee shops and pubs, talks at venues, book signings at local shops, and so forth, just as it includes online meetups and columns and posts shared from couches and kitchens and bedrooms and, well, probably bathrooms, too. I suspect we will remember this. The last year has, despite restrictions, still witnessed protests and marches, some righteous—for instance, marches against police violence—and some foolish—for instance, the anti-lockdown brigades.

We should take this moment to reflect on political writing as a collective act. The writer comes from a community, physical and digital. The writer produces material that goes into those communities, even if we do not all experience life in those communities the same—for instance, the extent and viciousness of abuse suffered by women, racialized folks, and so forth. Even during a pandemic, these spaces can be productive and powerful, serving as a part of the struggle for justice and accountability.

David Moscrop is a contributing columnist for the Washington Post and the author of Too Dumb for Democracy? Why We Make Bad Political Decisions and How We Can Make Better Ones. He is a political commentator for television, radio, and print media. He is also the host of Open To Debate, a current affairs podcast. He holds a PhD in political science from the University of British Columbia.