How Canada failed its farmers and agri-producers

Farmland in Saskatchewan. Photo by Joel Penner/Flickr.

Robert Jeffery—my paternal grandfather—lives on rural farmland in Bruce Mines, a small community in northeastern Ontario. His home, a quaint abode our family refers to as the “farmhouse,” is situated toward the end of Jeffery Road, a stretch of gravel aptly named in recognition of the once burgeoning Jeffery clan that resided in the area.

Although he himself is not a farmer, my grandfather is the product of an agricultural community. When he was growing up, most families in the region, including his own, managed small-scale farms to support individual households and the regional community. Today, many of his neighbours continue to rely on farming to earn a living, yet the future of the trade as a financially stable profession is more precarious than ever.

My grandfather has lived through some of Canada’s agri-food growing pains, experiencing firsthand the effects these shocks have had on rural communities. The dairy processing and delivery sector, for example, has changed beyond recognition in the nearly 50 years since Bob started out in a milk processing plant in Thessalon, a short drive from neighbouring Bruce Mines.

Eager to start earning a good wage and some independence from his large family of 12, he left high school early and took a job filtering and bottling milk in the Northshore Cooperative Dairy processing plant, a facility owned by the dairy farmers in the region. Unprocessed milk was shipped in from local farms in individual eight-gallon steel cans. After processing, delivery personnel would drive processed and packaged milk from regional plants to communities for retail sale. Milk processing plants were abundant in the 1950s and 1960s, Bob recounts, with at least 20 or so across northeastern Ontario alone.

After a couple of years working in the manufacturing plant, my grandfather started his career as a milkman in 1958. Rising well before dawn, he would drive throughout the Algoma District, delivering bottled milk to stores and homes from Thessalon up to Elliot Lake, a stretch of about 130 kilometres moving east along the shores of Lake Huron.

When Bob started his career, horse-drawn milk carriages for home delivery were being phased out for small delivery trucks. The job wasn’t anything glamorous, but it was six days of adequately paid work that provided a stable income and a benefits package to support a family of four. Along with my grandmother, who worked in retail, my grandparents eventually earned enough money to buy a cozy home along the riverbank in Thessalon. Growing up in this beautiful region along Lake Huron, my father and his brother have fond childhood memories of birthday parties, camping trips, long days spent fishing, and local cultural events.

Most families were by no means wealthy, including my own, but they never wanted for much. Parents supporting families with labour-based jobs, such as my grandfather’s, could provide the necessities of life and fund a few family vacations and luxuries every now and again.

Around 1965, the Northshore Cooperative was bought out by Model Dairy, a larger, but family-owned dairy processing company in Sault Ste. Marie, a city about an hour east of Bruce Mines. Bob continued working out of the Thessalon office, managing delivery in the region for Model Dairy. About a decade later, in 1972, American company Beatrice Foods purchased two dairies in the Sault, including Model Dairy. By the mid-1980s, the Thessalon processing and delivery office was closed, and Bob moved up to the Sault for work with Beatrice Foods. Around the same time, the American company phased out home delivery, cutting several jobs in the process. Bob’s seniority with the company secured him a position at Beatrice Foods as a wholesale delivery driver, a position he held until retiring in 2005.

Toward the end of his career, Beatrice Foods started contracting out jobs to Algoma Dairy Distributor before shuttering the Sault processing plant in 1991. The closure put nine people out of work, but Bob managed to maintain his delivery job, driving processed milk throughout a 60 kilometre stretch (between Desbarats to Iron Bridge) of the Algoma District. The milk, which my grandfather picked up in the Sault and drove to all the rural communities dotted along the map between Desbarats to Iron Bridge, was shipped from the new regional dairy processing hub in Sudbury, now the only licensed distributor for the region.

Sudbury is about a three-and-a-half-hour drive northwest of the Sault. Today, almost all the milk processing plants in the region remain closed (including the Sault and Thessalon locations, and one location in Sudbury), and shipping routes for transport drivers have grown longer and more grueling. Most farmers in the region have shifted away from raising dairy cattle and instead have opted for beef cattle ranching. Dairy farmers that remain find themselves shipping product further and further away, mostly down to southern Ontario for processing.

The localized milk industry in northeastern Ontario has all but disappeared. Instead, what we have today are vast monopolies, exemplified by Coca-Cola’s recent purchase of Chicago-based milk company, Fairlife. Fairlife milk first hit Canadian shelves in 2018, and in 2020, Coca-Cola acquired 100 percent of the firm. The same year it was introduced to the Canadian market, the soft drink conglomerate invested $85 million in a new Fairlife milk processing plant in Peterborough, where milk from all over the province (and neighbouring Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island) is now processed and shipped to retail.

Long gone are the days of milk sourced from local cows, processed at local plants, and delivered by local employees. Soon enough, a Fairlife brand decal will be synonymous with all milk in the region, homogenizing the products we reach for on the shelves at Superstore and Sobeys. The impending consolidation of the dairy sector is one example of a larger shift that has concentrated industrialized agriculture and expanded control along the agricultural value chain. The victims of this process are the very people who produce our agri-products and the once-thriving communities supported by agricultural livelihoods.

While it is important to avoid romanticizing agricultural models of the past—for example, many of today’s industry standards and processing technologies have advanced the dairy sector in positive ways—it is becoming increasingly apparent that our food system has changed since the start of my grandfather’s career, and perhaps not for the better.

Regrettably, in less than two generations, we have collectively severed our connection to food, altering the way it is grown and processed, thanks to forces that none of us, neither consumers nor farmers, can control. The impact of this shift on farmers and agri-producers has been largely negative. Corporate-aligned policies guiding our agricultural sector have facilitated a competitive environment that requires capital accumulation strategies for farmers to survive. While many farmers have gone into debt trying to build capital—by buying more land or equipment—farmers and agri-businesses with financial clout managed to concentrate the sector to the benefit of only a few major input and processing companies, shrinking the number of farms operating in Canada.

These dynamics have led to the creation and endurance of mega corporations that dominate Canada’s agricultural sector, while positioning twenty-first century factory farming as a highly profitable model for the owners of these enterprises. Private control over Canada’s agricultural sector now extends well beyond farms and into the food processing and retail space, effectively securing policy and regulatory influence all along the supply and value chain.

The societal and environmental harm perpetuated by this model is having grave consequences, expanding the power of corporate players at the expense of local producers—jeopardizing livelihoods that once existed within a well-balanced landscape of local producers that sustained regional economies for generations.

A farmer harvests wheat with a combine harvester against the light of the setting sun. Photo by Julian Stratenschulte.

Stressed out farmers and a dwindling countryside

Canada’s farmers are burdened with a heightened mental health crisis. Rates of stress, anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, and burnout are more common among farmers than other groups, given the nature of their profession (farmers have little control over “make or break” factors like uncertain weather or fluctuations in market prices and input costs). Forty-five percent of farmers surveyed in a 2016 study by the University of Guelph reported high levels of stress, and 58 percent were diagnosed with varying levels of anxiety. Over the last decade, account after account of loneliness, panic attacks, and depression among farmers made headlines in Canada.

Farmers encumbered by these mental health issues often face specific challenges such as unstable incomes and high input expenses (fertilizers, equipment, seed, land). Already high fertilizer costs are expected to rise, and between 2017 and 2019, most machinery costs per-acre increased around seven to nine percent. Larger machines, new technology, higher prices for parts, and increasing energy prices have collectively caused machinery and operation costs to rise in recent years.

Modern, highly computerized tractor equipment can cost more than an average-sized home in rural Canada—up to a million dollars for a John Deere tractor, especially if follow-up repair costs are included. Given these financial stressors, it is not surprising that the average net income for Canadian farmers over the last four decades has not kept pace with debt levels. Between 1980 and 2020, the average realized net income of farmers grew by 262 percent. By contrast, the average outstanding debt for farmers during the same timeframe increased by 666 percent. Debt levels loaned from private individuals and supply companies has increased by 410 percent between 1980 and 2020.

Farmers and agri-producers are also susceptible to environmental shocks beyond their control. Once seasonal weather patterns are increasingly unpredictable and unmanageable, outright destroying some yields and significantly impacting the types of crops farmers can grow. The breadth, scale, and severity of animal disease outbreaks on Canadian farms is growing, and while the agricultural community is implementing measures to protect against such diseases as hand-foot-and-mouth, an outbreak can ravage farmers financially.

Understandably, young farmers witnessing this cyclone of pressure and stress are reluctant to take over the family farm or enter the profession altogether. According to a study published by Canadian Food Studies in 2018, Canada is losing young farmers at twice the rate it is losing farmers overall. Between 1993 and 2018, the number of farmers aged 15 to 34 declined by nearly 70 percent. Four key structural factors were cited as deterrents to young farmers either continuing in or entering the agricultural sector: “low net incomes, an imbalance in market power between farmers and agribusiness corporations, increasingly unaffordable farmland, and corporate rather than farmer-focused state regulatory regimes.”

A more competitive and financially precarious agricultural sector is one factor contributing to rural brain drain, the exodus of young people from small, often remote, communities to large city centres in search of opportunity. The drain of human capital from northern Ontario no doubt affects the overall social and economic prosperity of small communities such as Bruce Mines and Thessalon. I could cite a series of statistics to illustrate my point, but to me, they pale in comparison to the countless stories I have heard at family reunions and holiday functions.

I grew up hearing tales of once vibrant cultural events, involving elaborate parades and activities for the seemingly infinite scores of children. I’ve listened to my dad and his brother recount youthful shenanigans at the local bar, and I can still remember the tamer, more family-orientated outings we took to the local mining museum in Bruce Mines. While these things surely continue in one form or another, times have changed for rural Canada. Small businesses are finding it harder to survive and residents are required to drive further and further away to meet medical needs, pursue secondary and post-secondary education, and access affordable groceries. Young adults looking for work are finding it increasingly difficult to secure a stable, decent-paying job in their hometowns.

Ron Bonnett, the current vice-chairman of the Farm Products Council of Canada, and who also happens to live up-the-way from my grandfather, described the scenario as a sort of “knowledge vacuum.” Chatting over the phone, Bonnett explained how young people have moved south for jobs, concentrating knowledge in these regions and away from specific sectors. One or two generations away from the farm has depleted the quality of knowledge required to enter the farming profession. Many resource-based sectors including mining and forestry are facing similar pressures. Bonnett is optimistic that a post-COVID world will spark a sort of rural-knowledge revival—a reference to the influx of people choosing to move back to rural regions as the work-from-home trend grows—and by extension a reconnection to land and agriculture as a profession. However, any sort of shift will be years in the making, and more importantly, if the current agricultural policy environment is not remodelled to provide farmer-centric supports rather than corporate-centric supports, a rural revival will not translate into an influx of young farmers returning to the land.

How did we get here? The dawn of austerity cuts and late-stage capitalism

One cannot comprehend the plight of farmers and agri-producers in Canada without understanding the economic and policy foundations that have underpinned the global economy over the past four decades. According to economist Thomas Piketty, writing in his recent book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, immense inequality in society is inevitable when capital’s share of national income (income distributed as interest, profits, dividends, and capital gains) exceeds the growth rate of the economy, which is measured by calculating the percentage change in value of all the goods and services produced in a nation during a specific timeframe. In other words, when the owners of capital (those who own the machines, ideas, land, and patents) earn substantially more than the end value generated by the capital and the labour producing the goods and services, the balance is tilted heavily toward capital owners, rather than labour.

A farmer working an irrigation ditch, April 28, 1950. Photo by H.E. Foss, courtesy University of Idaho Special Collections (94-4-3713).

This point is important to keep in mind because as Piketty has illustrated, this imbalance has existed throughout much of history, with the exception of periods in the late nineteenth and moving into the twentieth century. Both World Wars bolstered economic activity, and in tandem, the post-war advent of new regulations, tax policies, and capital controls stimulated an era of historically low levels of capital-income share in the 1950s. The balance between the end value generated by labour and capital and the amount funnelled to capitalists was relatively stable, a period that coincided with baby boomers and unfettered suburban growth.

Stagnation in the 1970s, however, was met with the proliferation of fiscally conservative policies around the world, spearheaded in part by the United Kingdom’s Margaret Thatcher and US President Ronald Reagan. These so-called austerity measures involved mass privatization and government deregulation, and the decimation of public institutions (public schools), social support systems (cooperative housing), and unions. Reduced expenditure on these social systems allowed governments to reduce taxes for capitalists, which were justified by the argument that such cuts would spur investment.

These neoliberal policies systematically gutted working class jobs from the economy. Austerity also meant that there was little or no fiscal support for these workers to aid in job transition. As in Canada, previously stable jobs in Britain’s mining and manufacturing sectors disappeared, in turn devastating the health and vibrancy of communities that relied on these occupations. While working class labour was gutted, massive tax cuts for capitalists funnelled money into the hands of the wealthy. This process brought about a massive growth in capital, and in this era of globalized finance, capital can no longer be said to belong to one country.

As economist Prabhat Patnaik explains, investments are made globally and driven largely by multinational corporations. Decades of such policies have generated a vicious cycle, whereby governments are required to maintain some level of austerity and capital-centric tax policies to attract investors. Subverting the neoliberal status quo would undoubtedly bring about domestic financial crisis, as investors retreat in search of a more favourable environment. The effects of this globalized economy are felt disproportionately higher in the Global South, as capital ownership is concentrated in the Global North and labour is primarily allocated to the South.

Regardless of where you live in the world, however, it is workers who have been forced to shoulder the negative impacts of austerity. As the working class was squeezed financially, fewer people could continue dining out at restaurants, go on vacations, buy books, or pay for higher education. At the same time, a growing percentage of people could not afford to meet their basic needs. Public institutions have eroded under the influx of demand.

Canada’s agriculture policy shift under neoliberalism

Agricultural policies of the past were designed to support farmers through stabilization price fixing mechanisms. These policies used commodity pricing on the market to determine funding needs. The Agricultural Stabilization Act (ASA), for example, was implemented in 1958 to fix commodity prices and absorb financial risk for farmers. The government-funded program provided subsidies to producers in every province during periods of low commodity prices. Nine commodities were listed under the act, and when the annual average price for any one of those goods fell below 80 percent of the average price, farmers were compensated for the loss. While imperfect, this method helped to level the playing field between small-to-medium sized farms and large farms by tying support needs to a comparative external measure, rather than an individual farmer’s ability to mass produce in a given year.

Considering that a farmer’s ability to produce each year is impacted by a variety of mostly uncontrollable factors, ASA style policies were effective because they provided farmers with income support regardless of the amount of goods produced. Moreover, farmers were not incentivized to expand production because support programs—designed to mitigate the uncontrollable effects of the abovementioned factors—provided funding based on market impacts to commodities, not the total value and amount of goods produced. What’s more, most farmers during this time were producing a larger variety of crops at a smaller scale. This meant that market impacts toward one commodity did not directly affect another. During this period, the strategic goal in the agricultural sector was not, first and foremost, to expand production for export—it was to feed local communities and provide farmers a living wage to do so.

As the world financial system grew increasingly interconnected and homogenous, however, the Canadian state implemented a series of policies that shifted support away from commodity pricing and farmer income support and toward capital accumulation and enhanced production. The goal of this shift was to leverage the agricultural sector as a strategic resource-base and sell this resource on the global market to increase the GDP. A research journal published by Canadian Food Studies reiterated this point, stating that “policies to maximize Canadian exports are part of efforts to make Canada a resource superpower. Food is one of those resources.” These aims are illustrated in the state’s commitment to grow agricultural exports.

In 1993, federal and provincial governments committed to doubling agricultural exports to $20 billion by 2000, and in 1998 they increased this goal to $40 billion by 2005. The latter target was proposed by the Canadian Agri-Food Marketing Council, an industry group that represented Cargill, Maple Leaf, McCain, and other big-name corporations. Today, Canada is the world’s fifth-largest agri-food exporter, and the most recent federal figures cited the sectors worth at $143 billion, accounting for 7.4 percent of GDP (2018 numbers). According to the Canadian Agri-Food Trade Alliance, Canada exports half its beef and cattle, 70 percent of its soybeans, 70 percent of its pork, 75 percent of its wheat, 90 percent of its canola, and 95 percent its of pulses. Over 90 percent of Canada’s farmers are dependent on exports. Such dependence means that farmers become exposed to international political vagaries. China’s ban on canola, beef, and pork, for example, drastically impacted domestic farmers. The ban was arbitrary, based on the geopolitical tensions between the two countries, and totally outside of the control or influence of agri-producers themselves.

The foremost policy implemented under the neoliberal economic framework was the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The policy, which was signed by Canada, the United States, and Mexico in January 1994, removed trade barriers between the three countries, creating a massive free-trade zone. To take advantage of this newly expanded market, Canada required a plan to ratchet up trade volume, which involved deregulation and transitioning the agricultural sector into an industrial operation. One year later, in 1995, the ASA program from 1958 was cancelled. Around the same time (roughly between the mid-1980s to the early 2000s), a series of income stabilization polices under the Farm Income Protection Act (FIPA) were repealed. Stabilization policies under FIPA provided payment to farmers when their annual net income fell below a historical average. These policies, unlike ASA policies, were based on personal income tax data limited to production margins, and therefore problematic because they did not consider assets and liabilities or input and output costs. Receiving financial benefits from these programs did not necessarily equate to a stable and viable income for farmers, as things like debt payments, capital costs, and fertilizer costs were not factored into eligibility requirements. However dubious, these policies did provide some support for farmers throughout the economic transformation of the latter part of the century.

Simultaneously, risk management policies, such as the 2003 Agricultural Policy Framework and the “Growing Forward” policy series (implemented starting in 2008), encouraged farmers to buy-in to the capitalist principles of bolstering efficiency and expanding production. For example, the AgriInvest program, which is under the most recent set of risk management policies, is a government scheme designed to incentivize farmers to supplement personal finances to absorb future shocks (like a bad crop year or export bans) and more effectively compete on the global market. Money contributed to this program is matched by the government, under the pretense that farmers will use savings to expand their asset portfolio by accruing more capital. Although these programs are marketed as risk mitigation strategies to increase capital gains in case of hardship, they are also indirectly designed to help farmers maintain additional revenue streams because farming is no longer a widely profitable industry on its own.

Supplementing agricultural-based income in Canada is common practice today. In fact, self-help guides on balancing multiple incomes streams are published in rural living and agri-based blogs. No doubt intended to be valuable to farmers, these types of publications ignore the deeper and more structural problem: farmers cannot earn enough money to make ends meet because the environment in which they are operating is designed to squeeze agri-producers to produce goods that can be sold cheaply on the international market. Looking just at aggregate numbers for indicators like exports and trade balances, Canada’s agricultural sector is extremely successful, productive, and efficient. The value of agri-production has nearly doubled since the early 1990s and food exports have more than tripled. But at what expense, and to whom is such growth directed?

Rising debt, labour shortages, and abusive practices in the agri-sector

The growth in metrics like national GDP and exports has been matched by the growth of a more troubling set of statistics:farmers’ debt, a growing mental health crisis, labour exploitation, rural brain-drain, and environmental degradation, to name just a few. Farmers are contending with rising input costs, soaring debts, volatile and depreciating commodity prices, and increasing land values. These factors, coupled with deregulation and policies geared toward mass production for export, have reduced the overall net income of farmers. Beginning with the farm debt crisis in Canada, agri-debt has nearly tripled since the early 1990s, and farmers paid $4.2 billion in interest payments in 2019. These figures are predictable, given the depreciation in crop and livestock value today compared to a few generations ago. Researchers analyzing this trend compared wheat costs, for example, from the Depression era until the mid-1980s alongside wheat prices since the middle part of that decade. They found that when adjusted for inflation, the price (in 2018 dollars) garnered for a bushel of wheat dropped by half, moving from a low of $10 prior to the mid-1980s to a low of $5 after that period.

The cost of farming is on the rise, too. The value of farmland has grown exponentially: $2,696 per acre in 2016, a nearly 40 percent increase from 2011. In recent years, a trend partly attributed to changing patterns in land ownership, including an increased concentration of land among fewer farmers, demand for farmland for non-farm uses, and an increase in ownership by investors. The National Farmers Union (NFU) is one organization among the many that has sounded the alarm on the “encroachment of industrial corporations into the business of primary food production through direct ownership, vertical integration and contract farming.” Unfortunately, it is not unusual for farmers to operate under contracts with agri-food corporations, which provide them with tighter controls over production methods and greater international market access without explicitly owning the farm and grappling with the liabilities. Moreover, higher land values, which are in part realized by the increased competition backed by investors with deep pockets, has translated into a dwindling number of farmers who can afford to purchase even small plots of land, let alone large, industrial sized farms. Not surprisingly, renting farmland is now a common practice in Canada, particularly among young farmers. According to Statistics Canada data, 50.6 percent of farmers under the age of 35 rented land in 2017, compared to 35.1 percent of all agricultural operators who rented land in the same year.

Migrant agricultural workers in Canada. Illustration by Bert Monterona for Action Canada.

Mounting debt and overwhelming costs have directly impacted small-to-medium sized farms, siphoning funds to a handful of farmers who have managed to create industrial sized operations. Twenty percent of Canadian farms (those with revenues near or above $500,000 annually) captured approximately 80 percent of net farm income in 2014 (the most recent year in data published by Statistics Canada). The net market income for farms operating in the lowest revenue bracket ($10,000 to $49,999) remained negative between 2003 and 2014, which was accompanied by a substantial fluctuation—a net income dip from -$63,017 to -$314,805—between 2003 and 2004. Comparatively, net market income for farms operating in the highest revenue bracket ($500,000 and up) increased from $1.6 million in 2003 to $7.4 million in 2014. What’s more, between 2003 and 2014, average net program payments provided to farmers decreased substantially, but the ramifications of this decrease were disproportionately felt among farmers with smaller operating revenues. Farmers with an operating revenue between $10,000 to $49,999 and between $100,000 to $249,999 experienced, respectively, a 76 percent and 80.6 percent decrease in funding supports, compared to the 59.5 percent decrease experienced by farmers in the $500,000 and above revenue bracket. This disproportionate cut in support payments to smaller farms is contradictory to the reality of the agri-sector, seeing as the proportionate bulk of farm operators between 2010 and 2014 were classified under the $10,000 to $49,999 revenue range (a total reaching 381,640 operators), compared to the 257,790 farmers operating under the $500,000 category.

The financially precarious nature of farming has in part facilitated an exploitative environment for migrant labour in Canada, and the policies that underpin this sector work to reinforce abusive practices. Labour shortages in Canada’s agricultural sector are common. In 2019, for example, the agri-sector recorded $2.9 billion in lost sales due to unfilled vacancies, an increase from $1.5 billion in 2014. To fill these shortages, farmers rely heavily on migrant labour. According to the Union for Agricultural Workers (UFAW), Canada has imported migrant labour for over 50 years, a system underpinning Canada’s immense agri-sector growth and competitive agricultural advantage on the global market. Despite their role in positioning Canada as an agricultural superpower, foreign workers have and continue to be underpaid, overworked, and often abused. “Canada’s industrial agricultural sector operates in a business environment that promotes the use of cheap labour,” said the UFCW. “Since Canadians are apparently reluctant to do agricultural work under current conditions, Canadian operators have looked abroad to source their labour needs.”

The UFCW has documented over 40,000 specific cases involving harassment and mental health issues involving migrant agricultural workers in Canada. COVID-19 has only exacerbated abuses and subsequent mental health issues, as Canada’s food production and processing “depends on low-paid, vulnerable workers—often migrant workers, recent immigrants and women—who not only do very difficult jobs, but also risk their own and their families’ health in the process.” Unfortunately, the policy environment has perpetuated the status quo, making it extremely difficult to bolster migrant rights. The Temporary Foreign Workers Program (TFMP) and the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) have expanded employer control, while restricting options for labour. These programs have provided Canadian farmers will a massive labour pool willing to work for undervalued wages, but at the same time, the terms of the policies have restricted labour mobility by providing workers with a closed work permit. These closed work permits essentially bind workers exclusively to one employer, with no room to negotiate better working conditions or higher pay. Said another way, migrant labourers cannot simply find a new employer if they are not treated well. Many of the people who pick the fresh fruit and vegetables we pile onto our plate for breakfast and dinner are forced to endure deeply precarious circumstances or be sent home without the pay needed to support themselves and their families.

Corporate gains and Canada’s ‘Big-Ag’ takeover

At another corner of the agricultural sector are large agri-corporations, a few of which have captured almost all value generated by the agricultural sector in Canada. According to a 2018 study, farmers produce roughly $60 billion per year in goods. On average, farmers keep less than $3 billion, while seed, chemical, fertilizer and machinery companies, as well as other input and service suppliers, retain the other $57 billion. In other words, the people planting the soybean seeds, being exposed to dangerous pesticides, harvesting the crop, shipping it to the manufacturer, processing it for retail, and selling the product to the public earn substantially less than the shareholders who own the seed variety, the chemical properties, the land and machinery, the shipping containers, the manufacturing plant, and the chain of grocery stores.

These financial flows allow these companies to further consolidate assets along the agri-value chain, and inevitably expand control over the agri-marketplace. Canada’s agri-food sector is largely owned by a handful of corporations, primarily foreign entities. Over 90 percent of Canadian beef is processed by either Cargill or JBS. Viterra (owned by the Swiss company Glencore), Cargill (America), and one privately owned Canadian company, Richardson, have dominated the grain processing sector. About 70 percent of pork is packed by Olymel and Maple Leaf Foods. Syngenta, Dow, DuPont, Monsanto, Bayer, and BASF, known as the “big six,” control 75 percent of agricultural input sales globally. Canola, corn, and soybean crops in Canada are dominated by Dow, DuPont, Syngenta, and Bayer. In 2010, 47 percent of Canada’s canola seeds contained genetically modified traits developed by Monsanto, and 46 percent contained genetically modified traits by Bayer. In 2018, Bayer acquired Monsanto, leaving 93 percent of Canada’s most valuable crops under the control of one firm. The bulk of soybean and corn proprietary seeds and chemicals are owned by either Bayer, Dow, DuPont, or Syngenta.

Kraft Heinz Canada (worth $13.46 billion CAD in 2017), Saputo Inc ($11.65 billion), and McCains Foods Limited ($7.67 billion) own the largest share of the Canadian food and beverage companies in Canada. Known as the “big five” in retail, Walmart Canada, Loblaw, Metro, Costco, and Sobeys, collectively control 80 percent of the grocery industry. The latter group have used their collective power to negate contracts signed with suppliers during the pandemic. According to Food in Canada, a food and beverage magazine, the big five have “added fees, failed to pay the amount agreed on or within the agreed-on timeline, announced retroactive contract changes, and taken other surprising actions.” Suppliers have organized, calling for the creation of a grocery “Code of Conduct” to prevent further mistreatment through a series of mandates between suppliers and grocers.

Independent grocers and small-scale suppliers have not been adequately represented in working groups dedicated to drafting this code of conduct. The code, as independent grocer John Pritchett puts it, is an attempt to protect rural Canada, independents, and consumers from the mess big-box stores and corporate agri-suppliers have created in the first place.

“And we’re supposed to wonder whether this is the ‘Made-in-Canada’ solution that we need,” added Pritchett. “We need a strong code that addresses fair supply, addresses fair costing, and has real tangible enforcement that can apply to all of us. I don’t need something special, I need something fair, so that I can be fair across all the communities that I serve. Until we do that, we won’t protect the Canadians that we serve, and that’s just not good enough.”

“I’m not looking for a handout,” joined David La Mantia, store owner and operator of La Mantia’s Country Market Fresh in Lindsay, Ontario. “We are fully prepared to compete; we just want a somewhat level playing-field to compete on” (Pritchett and La Mantia both attended an online forum discussing the impacts of COVID-19 on agri-food supply chains. These quotes were pulled from that webinar).

Popular counterpoints favouring the corporate consolidation argument tend to champion corporate investment into regions and job creation. However, these arguments fall short when contrasted with the gargantuan income gap that exists between the shareholding, managerial elite (CEOs and the like) and regular employees, as well as the dismal labour supports provided to these workers. Let’s begin with the former issue. In 2017, Dow and DuPont completed a $130 billion merger to form DowDuPont. Despite expressed concern from stakeholders in Canada’s agricultural sector regarding the merger, it went ahead only to split into three companies—Dow, DuPont, and Corteva—a few years later. Leading up to the merger and following the split, these companies collectively eliminated 18,000 jobs, closed 82 factories in North America (some of which were in Canada), and cut research and development funding by 40 percent.

Meanwhile, prior to the merger, in 2014, the companies spent more than “$3 billion on share buybacks to prop up stock prices,” issuing almost as many new shares. This process inflated the value of the companies’ stocks, conveniently increasing the worth of Dow and DuPont right before a corporate merger. Perhaps the intentions behind this merger are less nefarious, and it should be said that this scenario is entirely legal, and yet the amount of money collected by the CEOs of Dow and DuPont both leading up to and following the merger should generate a healthy amount of skepticism.

Andrew Liveris, the outgoing Chairman of DowDuPont Inc., received $65.7 million in 2017 from the merger, $42.7 million more than his allotted compensation in 2016. DowDuPont’s CEO, Ed Breen, made over $13 million in annual salaries in 2018. For comparative purposes, the median average of the company’s (DowDuPont) employees in 2018 was $78,835. Post break-up, Breen, who is still the CEO of DuPont, cleared over $20 million in total compensation in 2019. Dow’s current CEO, Jim Fitterling, received over $12 million in 2019. Fitterling and Breen combined were given more than $26.5 million in stock values in 2019.

The infinite and drastic expansion of shareholder value in these mega-corporations is made possible by consolidating and controlling the agri-sector. Through securing a broader control of the sector, via acquisitions, mergers and lobbying power packed by deep pockets, corporations have managed to expand production for profit, while simultaneously exploiting labour. Said plainly, these extra “earnings” aren’t trickling down to the labour pool in any meaningful way. This transgression is further emphasized as corporations continue to exploit and undermine labour by supressing and destabilizing union movements and normalizing poor working conditions. Cargill, Canada’s largest meatpacking facility, is under investigation for criminal negligence regarding a COVID-19 outbreak, after multiple people died from contracting the virus at work. Local union representatives from the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 401 branch notified Cargill of a confirmed COVID case in April 2020, providing a series of recommendations to address the issue, including a plant closure and ensuring employees had access to financial assistance if required to self-isolate. Despite strong opposition from employees to continue operations, Cargill did not close the facility. Only after two employees died from the virus did Cargill act. Even prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, working 18-hour days at the packing plant was common practice for employees. Hiep Bui, one of the women who passed away from COVID-19, had dedicated 23 years of her life working long shifts for Cargill. Sadly, Cargill is not the only meatpacking plant to have hundreds of COVID cases linked to malpractice.

Walmart has a notorious history of supressing unionization efforts around the world, including here in Canada. Employees at a Québec Walmart made history in 2004 after managing to unionize. A few months later, however, Walmart management worked to actively undermine union organizers, create divisions between employees, and discourage any sort of discussion or corralling around the common cause of stable working conditions, paid sick leave, and a living wage. Instead of granting these basic items most of us take for granted, the Walmart in Jonquière, a borough in the city of Saguenay, shuttered its doors in 2005, cutting 225 jobs in the process.

While some Walmart locations in Canada have unionized, the corporate giant has continued with efforts to prevent the creation of new and the destabilization of existing unions by leveraging its immense wealth and legal connections. Sobeys recently offered its employees in Nova Scotia a COVID bonus. Depending on hours worked during a lockdown, employees could earn an extra $10 to $100 per week. Although perhaps a small consolation prize for Sobeys employees in Nova Scotia, it is worth pointing out that Empire Co. Ltd—the parent company of Sobeys, Safeway and FreshCo, collected $181 million in 2020’s fourth quarter alone. These “earnings” came after the company cut its bonus pay for frontline staff across the country. Predictably, Sobeys is also anti-union.

These corporate-aligned policies have been made possible, and made worse, by international trade negotiations. The NFU summarized this paradox and its repercussions:

As terms of trade agreements are ratcheted up, each one building upon the last, the power imbalance intensifies… The imbalance between these global agribusiness corporations and farmers is severe. Competition between companies within the country is disappearing as global corporations pursue ‘competitiveness’ with other giants on the world stage by taming governments and using their market power to enforce exploitative conditions on the producers who supply them with the products they trade.

Putting it all together, we have seen how Canada’s agricultural sector was established on a neoliberal foundation that incentivized corporate investments, functioning as a mechanism to expand production and compete globally. This relationship in turn has reinforced a vicious cycle of corporate concentration and control over the agri-market coupled with government complacency. Expanded export production has contributed immensely to Canada’s overall GDP growth. Indeed, the numbers illustrate a pretty picture, but there is a lot of grey coming through that we have failed to see, or perhaps are reluctant to acknowledge. Fused with deregulation and support service spending cuts in the agri-sector, farmers find themselves straddled with exorbitant debts or pushed out of the market altogether. Financial reinvestments to support farmers leaving the sector or to assist farmers entering the industry are virtually obsolete. Rather, farmers navigating this environment are encouraged to adopt risk mitigation strategies, which typically entail methods of accruing more capital or maintaining additional revenue streams to expand production to compete more effectively and to stay afloat in an increasingly unprofitable business. This dynamic of squeezing production labour has seeped into other sectors along the agri-value chain, including manufacturing and food retail. Within these sectors, corporate control has created a highly competitive environment where small businesses cannot compete, and has led to the exploitation of labour, mainly through the suppression of union movements.

The unfortunate ramifications of this cycle are manifested in several ways: dwindling rural communities, migrant labour exploitation, larger but fewer farms, a generational disconnect from the land, and perhaps most egregiously, a growing divide between those who own the means of production and those who produce. Undeniably, the gains collected through various forms of corporate capture have not translated into better paying, more stable jobs along the agri-food supply chain. Instead, most gains have found their way into the pockets of corporate shareholders and a handful of industrial farmers.

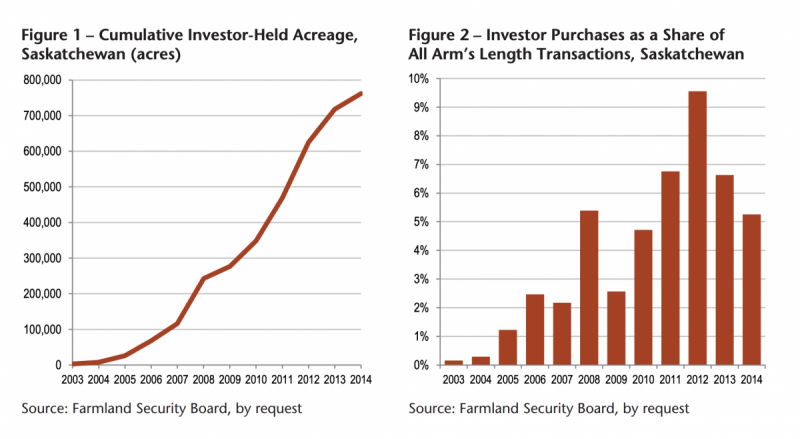

Graphs from “Who is Buying the Farm? Farmland Investment Patterns In Saskatchewan, 2003-14” by André Magnan and Annette Aurélie Desmarais for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Food security, food sovereignty, and democracy

Beyond some of the commonly discussed reasons—the psychological and social ramifications of societal disconnect from nature, impending ecological collapse and environmental degradation, and the moral argument (agri-labourers deserve respect and a living wage)—the transformation of Canada’s agricultural sector has significant implications for our long-term food security and food sovereignty, as well as the social welfare of those who feed us.

Starting with food security, a significant percentage of agri-goods in Canada are sourced as raw materials, shipped abroad for export, and often sold back to Canada as a finished product. Canada is simultaneously the fifth-largest food exporter and the sixth-largest food importer globally. In 2014, 52 percent of Canadian fruit and vegetable production was exported, even though Canada is a “significant net importer of horticultural products, beverages, certain fish products, and processed goods.” Ontario, for example, is a net food importer, spending $10 billion more than it exports, and many of these imported products include raw resources grown in the province. This process may appear counterintuitive, but it has contributed to total agri-sector growth (and therefore Canada’s total GDP growth) by outsourcing the processing and manufacturing costs (typically to the Global South where labour costs are cheaper). While this framework has positioned Canada as a resource superpower that benefits from exploitative labour practices abroad, it has also made the country susceptible to supply chain vulnerabilities when faced with disruption.

COVID-19 is an example of a disruption that can impact the agri-food supply chain, and although Canada has managed to maintain a relatively steady supply of goods during the pandemic, these types of global disruptions are expected to grow in both severity and frequency. Continued global shocks, such as a global health crisis, will undoubtedly impact the flow of goods between countries and the ability of manufacturing-based countries to produce goods. For example, if Canada does not have the capacity (both the skilled labour and the infrastructure) to process raw agri-resources into edible food, the country could face food shortages. Perhaps these stressors to our agri-food chain are subconsciously understood by average consumers in Canada, which may explain the wave of panic buying that ensued during the onset of the crisis.

Current and future health pandemics aside, the homogenous and extractive nature of our global agricultural system has rendered farmers more susceptible to other types of shocks, challenging the country’s overall food security. Our agri-system is monocrop-based, adhering to the high-input, high-output principles of industrial efficiency for export. Given that a dwindling number of farmers have prospered under this model, a shock to one of Canada’s key crops could lead to a depleted stock for both export and domestic consumption. Fewer farmers are farming, and the farmers that are producing are growing a handful of financially advantageous crops for export. Relying on these few crops and few farmers increases the impact of disease or crop failure across the agri-sector. For example, an animal disease outbreak in Alberta cattle country could quickly exhaust livestock, or a Bayer-based corn crop in Saskatchewan could build a resistance to Bayer-based chemicals and fail.

Consecutive disruptions like these ones will increase Canada’s reliance on imported food. While some may not see the harm in expanding imports, the problem is that most of the world has transitioned to this homogenous, “efficient” model of production. Most other countries are also experiencing increased cases of livestock disease and crop failure, scenarios that are directly linked to the expansion and intensification of a high-input, high-output agri-sector. This link is derived from the very nature of today’s agri-sector as a simultaneous contributor to climate change and one that is highly vulnerable to the worst impacts of anthropogenic warming. In other words, the resource pool from which Canada can pull from (both abroad and at home) is highly unstable because of how a heating climate and an exploited growing environment have affected these resources (through increased disease and crop failure, for example). At the same time, however, rising temperatures and soil depletion are both symptoms of this resource-intensive agri-model.

Our ability to choose what and how we eat is also threatened under the current industrialized agri-model. Food sovereignty is the control over the production, processing, and marketing of food, a space providing room for community-governed, regionally based food networks. The globalized food system has homogenized the human diet, creating serious consequences for human nutrition, and undermining the role food plays in culture. Concerning the former, studies have linked a growing reliance on a few food crops to a global rise in obesity, heart disease, and diabetes, even within countries where food intake is constrained. Moreover, studies exploring the effects of climate change and industrial agriculture on remote communities have illustrated how a depletion of traditional and regional food sources and food gathering practices has escalated community reliance on globalized agri-supply chains.

Many of Canada’s Inuit and First Nations communities in our northern regions, for example, have cited a decrease in traditional knowledge about hunting and gathering practices of regional foods. Meanwhile, long transportation routes, increased shipping costs, and harsh climatic conditions have rendered the distribution of fresh and nutritious foods to northern regions difficult. The fresh food that does make it up north is very expensive, leaving the high-fructose, high-processed alternatives often the only viable option for consumption. Beyond nutrition, we should care about food sovereignty because food largely defines the many unique and vibrant cultures that comprise Canadian society. From north to south, east to west, families across the country have gathered to enjoy culinary favourites inspired largely from the communities and cultural contexts in which they live. Severing this connection between food, the regional environment, and the local culture can have profound implications on the social and psychological fabric of a community. Perhaps we understand what is at stake on a more intuitive level, a scenario fueling our starvation for nourishment and connection despite an abundance of food.

Lastly, we should care about farmers and agriculture because a tilted scale toward capitalists jeopardizes our ability to actualize democracy in the food sector. Our food system and the labour that has underpinned it over the last several decades lies proxied to a much larger and more systemic problem: the disappearing middle class. The flourishing of inequality has undermined democratic participation in all facets of society, as politicians are beholden to the interests of large corporations, not the public. However, this devaluing of democratic principles—which has extended beyond federal elections and into union organizing, community-engagement efforts, food banks, community garden and farming initiatives, and the like—is perhaps most apparent in our food sector. Tragically, we are witnessing this demarcation between who may and may not participate in the development of our food system reflected on our dinner plates, as the wealth gap is revealed by those who can afford to eat healthy, organic food and those who cannot, by those who produce food and those who own the rights to food.

Fairlife first hit Canadian shelves in 2018. Coca-Cola acquired the company in 2020. Photo courtesy Fairlife.

Coca-Cola milk processing plant a win for farmers and democracy?

Corporations are designed to operate and compete in an economic framework that requires continued capital accumulation and political influence to survive. Given these principles, and everything I have outlined in this article, we should not glorify Coca-Cola’s control over Ontario’s dairy sector. One of the primary goals of the Fairlife milk processing plant in Peterborough is to maximize production with the intention to add to export sales. Enhanced production will undoubtedly help some farmers financially, but it will crowd out many small-to-medium sized dairy farmers that cannot compete, generating heightened unemployment, an influx of debt (and therefore interest payments to owners of capital), and increased rates of mental illness and undue stress for farmers.

Many of these small-to-medium sized dairy farms in rural communities will be abandoned, and with no adequate job programs to absorb rising rates of unemployment, young professionals will flock to large cities in search of work. Rural brain-drain from these communities will sever generations of agricultural knowledge and hinder the social and economic stability of rural Canada. Perhaps a few lucky people will land contracts at the new Fairlife processing plant, where 35 new jobs are expected to be created. Information on whether these jobs will be unionized was not readily available at the time of writing. Regardless, Coca-Cola has a history of anti-union violence and exploitation in other countries. In Canada, some Coca-Cola processing facilities are unionized; however, employees at a plant in Calgary recently went on strike to demand better job security and an end to labour outsourcing.

Meanwhile, Coca-Cola will continue to pride itself on using Canadian milk, but for how long this remains the case is not etched in stone. Coca-Cola will pursue capital accumulation and thus control of the dairy sector, lobbying for policies that continue to prop-up the political-economic framework that is most advantageous to its shareholders. And Canada will concede, attempting to ratchet up its GDP growth (namely through exports). As the scale is tipped further and further toward multinationals like Coca-Colas, democratic intervention will become increasingly difficult, perpetuating the vicious cycle of relaxing policies to accommodate corporations to generate growth at the expense of the middle class. Indeed, with the right amount of political clout and financial weight, it is not out of the realm of possibilities that the regional net for resources (in this case unfiltered milk) will continue to expand beyond Canadian borders and into neighbouring American states, thus further increasing competition for dairy farmers. Under increased competition, it would not be unusual for desperate dairy farmers to leverage exploitative practices to cut costs and stay afloat.

This process has unfolded in other areas of the agri-sector, and it is likely to happen again. While this process has unfolded, the arena for public debate has grown smaller and more politically and economically influential. This arena will grow tighter still, as rural communities struggle for supportive policies and young talent; as farmers and agri-producers struggle to earn a living wage and find adequate union representation; as unions themselves find it increasingly difficult to challenge corporations with expensive lawyers and infinite financial reserves; as consumers are sold a handful of products owned by the same company, and as methane gas levels continue to rise alongside enhanced production.

Our failure to support the people who grow our food has restricted our ability to actively participate in a sector of society that impacts, quite literally, everyone (we all need to eat) and everything (its continued existence is fundamentally connected to health of the environment). Restricted public debate around the legitimacy of the current agri-model will continue to compromise food security and food sovereignty. Said bluntly, our food sector is not just unsustainable and exploitative, it is fundamentally undemocratic. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Building a more equitable, sustainable, and supportive agri-sector

Addressing the political economy, as it is structured today, must be a key component of the solution to Canada’s agricultural future. Clean technology programs, the latest series of investment initiatives funded by the Government of Canada, aim to “support research, development, and adoption of clean technologies through investments in, and promotion of precision agriculture and agri-based bioproducts.” While these technologies will help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and funding initiatives by the government will assist farmers in purchasing these technologies, these programs seemingly ignore the root cause of the environmental problem (industrial farming) and the political-economic framework (the green tech industry will likely consolidate, creating one more faction of corporate control for farmers to contend with).

On the consumer side, boycotting the Walmarts of Canada and exclusively supporting local farmers’ markets and grocers when possible is a great idea, but this choice is already one of privilege and simply not practical for millions of Canadians. Both avenues are mere band-aid solutions to the structural and systemic foundation on which we have established the food industry, as they do not fundamentally address the effects of unrestricted, concentrated capital flows on farmers, society, democracy, and inequality. Sustainable and systemic change is possible, but our efforts as informed consumers and technological evangelists must be tied to our democratic responsibilities of supporting farmers and agri-producers along the value chain. We must put pressure on our governments to create and implement policies that support agri-producers and farmers, not corporations, and we need to move away from the industrial-sized agricultural model.

Localizing our agri-system and creating an environment that is producer-focused is not only possible, it’s already starting to happen. Communities in the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary worked with the provincial government of British Columbia to establish “food hubs.” These foods hubs are designed to assist small-and-medium sized producers by providing access to shared food and beverage processing space and equipment to increase production and sales. Producers using these hubs rely on locally grown and raised products, everything from cattle and chickens to veggies and fruits. Creators of the project are now drafting plans to implement a local distribution system, bottling factory, testing lab, and business marketing and export supports. Producers are keen to tap into new, local markets by expanding exports into the Okanagan (interior British Columbia).

British Columbia’s provincial government announced in February 2021 it will be investing around $750,000 toward a food hub across the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary (RDKB).

Momentum for the food hub project was kickstarted during the pandemic, when the heightened risk of international food supply chains became apparent. “People are starting to realize we actually have to figure out how to feed ourselves again, and this is the beginning of that,” said Sandy Mark, interim manager of the Boundary Food Hub. These hubs will help to feed British Columbians by becoming a net producer for the region, instead of a net importer. Through localizing the supply chain from the raw resources to the packaged goods, these two first hubs in Rock Creek and Greenwood are establishing a food system that is more secure and more financially viable for the producers themselves. According to Barry Noll, the Mayor of Greenwood, the initiative has provided “an economic boost” for the area. A total of $5.6 million has been earmarked under the StrongerBC Economic Recovery plan to expand the BC Food Hub Network. Three additional food hubs are currently operating in Vancouver, Surrey, and Port Alberni, with additional hubs in Quesnel and Salmon Arm expected to open later in 2021.

Beyond Canada’s borders, initiatives to support farmers and producers along the agri-value chain are making headway in Germany. The RegionalwertAG Freiburg is a civil stock corporation supporting small-and-medium sized regional businesses through the agri-production, manufacturing, and marketing processes. The goal of the corporation is to promote food sovereignty, by creating more room to maneuver and participate in the agricultural sector and strengthening the quality of life in rural areas. The corporation functions by encouraging farmers, producers, engaged citizens, and local businesses to purchase regional shares and corporate participation rights. RegionalwertAG then invests money in shareholder capital, land, buildings, and facilities along the agri-value chain. These investments are essentially partnership agreements with local farms, retailers, processors, and the like. There are acute differences between this corporation and the other firms discussed in this article, however, including limits to capital accumulation and returns on investments. The profit returned to the investor includes dividends and the value of the investor’s socio-ecological contribution. In other words, investments are made not just to secure monetary value, they are made to also promote things like the maintenance of food quality, the preservation of soil fertility, job creation, biodiversity conservation, and to strengthen the security of regional agri-supply chains.

Moreover, there are rules surrounding shareholder rights. For example, shareholders have voting rights proportional to the stock they own, but no one person may acquire more than 20 percent of the voting rights. Any sale of shares to another person must be approved by the board, and investment projects with local partners are decided collectively. The approval of these investment projects is contingent on partners meeting specific criteria (they must operate regionally or maintain ecologically responsible practices, for example). Shareholders are also obligated to commit to an investment period of, at minimum, seven to ten years, and they must provide a two-year notice period to close-out an investment contract.

These rules are strategic, helping to provide agri-food businesses with continued financial stability, while also preventing shareholders from excessively consolidating and expanding assets to make a quick buck, as was the case in the DowDuPont merger of 2017. Perhaps the biggest advantage of RegionalwertAG is that it provides the financial backing of a corporation to compete in a capitalist market with firms like Coca-Cola and Walmart, while centreing its goals around farmers, producers, and the environment.

What kind of society will we leave for future generations?

During our many long conversations discussing this article, my grandfather talked about the myriad changes he has witnessed throughout his career. Some were positive, like the improvements made to milk processing. Technology, such as refrigerated trucks, helped to improve the shelf-life of dairy products and usher in stricter processing standards like cleanliness. And yet, I felt as though many of the changes he discussed reinforced the reality that we’re living in a society of disposability, both with respect to the environment and our neighbours. My grandfather talked about the waste generated from the introduction of plastic packaging, and he acknowledged his luck as perhaps the last of a generation who will live out his twilight years supported by a pension secured through nearly a half-century of manual labour work. Although a quiet and stoic man, I could hear his concern when we talked about the impossibility of future generations supporting a family of four by working in a similar occupation today.

There is no doubt that the agricultural sector has drastically changed from the early days of my grandfather’s life. Overall, this shift has not been positive for most farmers and labourers along the agricultural value chain, and their dwindling status stands in stark contrast to the financial gains of a few corporations. The system is not working for farmers, the very people who grow the food that keeps us alive. Continued exploitation of the labour and the land will not only lead to further inequality, but to a collapse of the food system itself.

Cassandra Jeffery has a graduate degree in public policy and global affairs from the University of British Columbia. She is the recipient of a Simons Award in Nuclear Disarmament and Global Security, and she is currently working as a research assistant to analyze energy policies in North America and Asia.