Loblaw sees ‘profit improvements’ in wage and benefit cuts

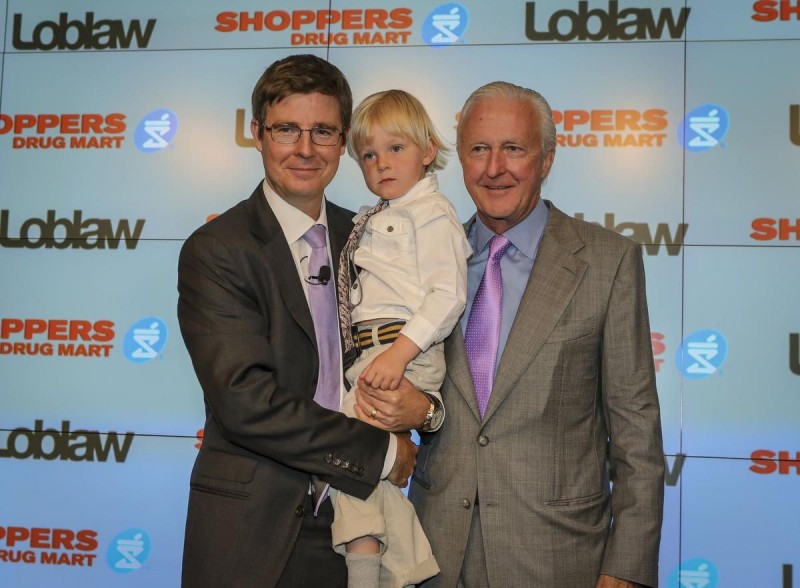

Loblaw makes its profits by paying workers poverty wages, writes Mitchell Thompson. Photo by Lars Hagberg.

Twice since the pandemic began, the billionaire CEO of Loblaw Companies Ltd. has risked job action by the company’s low wage workers in a bid to cut their $2 pandemic premium pay. More than just cutting costs, this is about keeping workers desperate or—in the company’s words, “flexible.”

On Monday, 10,000 Alberta Superstore workers ratified a deal after voting 97 percent in favour of striking against pandemic pay cuts, inaugurated last June.

In June 2020, Loblaw’s CEO, Galen Weston Jr., wrote to announce workers were getting a pay cut. Their $2 per hour premium “hero pay” was ending. The CEO promised workers the company’s stores are “operating safely and effectively in a new normal.” And, lest he seem cold, he ended his letter with: “Your safety and the well-being of our colleagues remain our top priority. Be well.”

Since that time, Loblaw’s stores have reported dozens of COVID-19 outbreaks, including at 30 Superstore locations. The “hero pay” was not restored.

Bigger cutbacks, bigger profits

United Food and Commercial Workers Local 401, which represents Superstore workers in Alberta, pushed the company into dropping most of its demands for concessions. But, as the union noted, “Loblaws made a choice with their final offer about how they would ultimately value their employees.”

From the accounts published thus far, the proposed “modest” wage increase is far below $2 per hour.

The pay cut provoked a 12-week strike by Dominion workers last summer. The workers, unfortunately, only won a $0.35 increase in the first year.

Meanwhile, the wage cut laid the basis for a “banner year” for management. According to the company’s June 2020 Q2 report, the wage premium cost Loblaw $180 million for its 220,000 workers. By contrast, as its 2021 management proxy noted, it spent $548 million on “share repurchases.”

It may seem strange for a company this profitable to risk significant labour “disruptions” over a $2 per hour wage rise. But Loblaw’s wage cutting efforts persevere through strikes not merely to balance costs. The company keeps its wages low also in the name of “flexibility”—the ability to cut costs later by keeping its workers desperate.

Where the Weston family’s wealth comes from

In 2013, Toronto Life described the Westons’ Vero Beach residential property, known as Windsor, as 168 hectares of beachfront streets, traversable only by golf cart, named after the family and its corporate subsidiaries (Wittington, Renfrew, etc).

“Windsor, thanks to the Weston’s connections,” the magazine observed, “has become a gathering place for an international community of jet-setting plutocrats who aren’t defined so much by nationality or political persuasion as corporate allegiances. They are a nation unto themselves.” Listed among the visitors were the royal family, James and Julia Ogilvy, the Swarovski family, former Amway CEO Dick DeVos, Michael Wills, Andy Pringle, Conrad Black, Peter Oliver, André Desmarais, and others.

In the first quarter of 2013, George Weston Ltd., the parent company of Loblaw Companies Ltd, raised its dividend by more than 33 percent. In its 2013 annual report, the parent company reported an increase in its net earnings to $907 million.

Also in 2013, Loblaw Companies Ltd. provoked strikes at its Superstores in Alberta with demands for sharp hours reductions and pay cuts of up to 40 percent for new hires. After 97 percent voted to fight the cuts, the company’s concessions were beaten back by a three-day strike of 8,500 workers. At the end, they won small wage increases for full- and part-time staff and improvements in health and benefit coverage.

This is part of a long-term pattern for the Weston’s enterprise, across its chains.

W. Galen Weston (right) with his son, Galen G. Weston, and grandson Graydon during a 2013 news conference to announce the purchase of Shoppers Drug Mart. Photo by David Cooper/Toronto Star.

From expansion to retrenchment

From Loblaw’s founding in 1919, through the rapid purchase of shares by British Conservative MP and biscuit magnate W. Garfield Weston in 1947 and following its post-war expansion, Loblaw and the Weston enterprise found their advantage in scale.

University of New Brunswick Professor Barry E.C. Boothman notes, in his history of the period, the sales average per grocery store jumped across Canada from $68,530 in 1939 to $168,930 in 1945. Boothman wrote this expansive method was generalized by competition:

Government data suggests that approximately 58 percent of food chain stores increasingly employed the ‘combination’ format during 1930 but this expanded to 80 percent by 1945. The manoeuvre converted food stores to the equivalent of department stores, ‘one stop shopping’ facilities.”

In 1955, after Weston acquired the company’s controlling shares, Maclean’s noted Loblaw already dominated grocery retail in Ontario with 156 stores worth $220 million. Its only competition, the magazine noted, was Dominion Groceries, headed by Bill Horsey with the backing of Argus corporation founder E.P Taylor. “The fight involves bigger sleeker stores with huge volumes of food moving quickly,” Maclean’s reported.

New lines of goods from hardware to hair lotion, slick selling techniques and a scramble for choice sites as the grocery giants follow the motor-car trek to suburbia. It’s part and parcel of postwar living, with its five-day week, refrigeration, frozen foods, cake mixes, prepared salads and packaged meats.

Loblaw’s expansion continued through the post-war period. It eventually superseded Dominion even as the latter was, by Loblaw’s own account, offering lower prices. In 1969, the Globe and Mail reported the company was dominant in retail and wholesale. In these sectors, traditionally marked by much thinner margins, the company’s profits increased 24 percent with $1.6 billion in sales.

By the mid-1950s, the company had already settled with several Congress of Industrial Organization locals. In his history of UFCW Local 401, Defying Expectations, Jason Forster writes, through this post-war boom, Loblaw, as a near-monopoly, opted in some cases to even recognize drives voluntarily to buy peace and cut across more militant organizing efforts. The same, in many cases, went for modest wage increases.

But this would not necessarily last. Even in the Globe article, Weston is quoted warning about lower-cost US retail chains. And, after another expansion in the early 1970s, margins were tight again even as the company emerged as one of Canada’s largest private sector employers.

Then-CEO, Richard Currie, was, according to his account, put in charge by Weston to do what was needed to make the company profitable again. The reality, he argued, is that expanding scale only increases profitability if demand also continues to grow.

“We had a problem,” wrote Currie in a 1993 speech transcribed by the Ivey Business Journal. In 1976, the company reported $3 billion in sales but only $3 million in “retained earnings.”

Quoting Shakespeare, Currie said: “‘The evil that men do lives after them.’ It certainly does, and particularly in two areas, first in labor costs and unionization, and second in real estate.”

The enterprise needed cash and, Currie said, after selling redundant real estate and “closing stores,” the company’s workers had to accept cuts, too. “Weak management had allowed the store asset base to erode and had provided fertile opportunities for labor unions.” By contrast, Currie said:

Profit improvements in the 1990s are likely to come primarily from bottom-line cost reductions and lowered breakeven points rather than from the top-line sales and margin expansion strategies much more common in the 1970s and 1980s.

The cost of goods sold in food retailing is the largest cost in the business—about 80 cents out of the sales dollar—and as we all know, buying is a pure variable cost. Any improvement in buying has the potential to flow straight to the pretax profit line, so the financial as well as commercial importance of proper buying cannot be overestimated. Labour costs are the next largest cost in the food retailing business… It remains astounding to me that so many food retailers have spent their careers spreading fixed costs when there are so few to spread. What there are plenty of is variable costs—in fact about 11 or 12 of them for every one of fixed.

Spreading “variable costs,” as the company noted, meant provoking four “high-profile strikes” across Ontario and Québec at the end of the decade.

The company’s 2003 annual report noted its average return on equity rose from just over 12 percent in 1999 to over 18 percent in 2003. The report credited “closing higher cost facilities” and restructuring its workforce for a “low cost operating environment” with helping manage its sales challenges. Looking forward, the company warned about future “work stoppages” as it struggled to compete against “non-union competitors” which “may benefit from lower labour costs, making it more difficult for the company to compete.”

In 2006, Galen Weston Jr. took over as CEO in advance of, as Maclean’s noted, “an imminent strike by unionized workers in Ontario.” Management wanted to reclassify stores in an effort to cut wages and benefits, until a last-minute agreement averted the strike and the cutbacks. That delay, however, only lasted until 2010, when 1,700 workers in Sarnia, Chatham, and Windsor were moved to strike against wage and benefit cuts of up to 25 percent. At the time, Loblaw’s public relations vice president justified the cuts by saying it would help the company obtain “operational flexibility.”

Back in 2018, Loblaw’s management clarified what that meant. The board suggested shareholders reject a credit union proposal to pay its workers a “living wage”—described in the proposal as “the income necessary to support families in specific communities.” Notably, the directors opposed the motion because it would “oversimplify” the ways in which Loblaw sets compensation “and restrict its competitive flexibility.”

It is further notable that, last year, around the same time that Loblaw introduced its pay cut, Weston co-authored a report for the Business Council of Canada entitled “We’ve Flattened The Curve, Now What?” It complained the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and other pandemic supports were making workers too comfortable to return to low wage work:

CERB is extremely expensive, and companies across industries are finding it difficult to restart if employees lack incentives to return.. Adjusting the program is more complicated than it seems, the policy design issues are genuinely intricate, but adjusting CERB and other programs to be more targeted and provide greater incentives to work is crucial. Employers clearly have a key role along with governments. There is scope here for fresh ideas and new thinking.

Loblaw guarantees its profits and its security as a near-monopoly by continually suppressing the demands of its workers—this is the source of the Weston family’s wealth. Desperate workers tend to tolerate wage cuts to make them more desperate still. Every cut won will be used to aid the next one.

Mitchell Thompson is a writer, editor and occasional radio producer based in Toronto.