Newfoundland university under fire for weaponizing code of conduct against student activist

Two leading civil liberties experts are calling Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador’s response to one of its students following a recent protest “extreme” and “inappropriate.”

Representatives from the Canadian Civil Liberties Association and the Centre for Free Expression at Toronto Metropolitan University say Memorial may have violated the young activist’s constitutional rights, and that the university’s use of a policy intended to create a safe environment is part of a troubling trend where similar policies are used to silence student dissent.

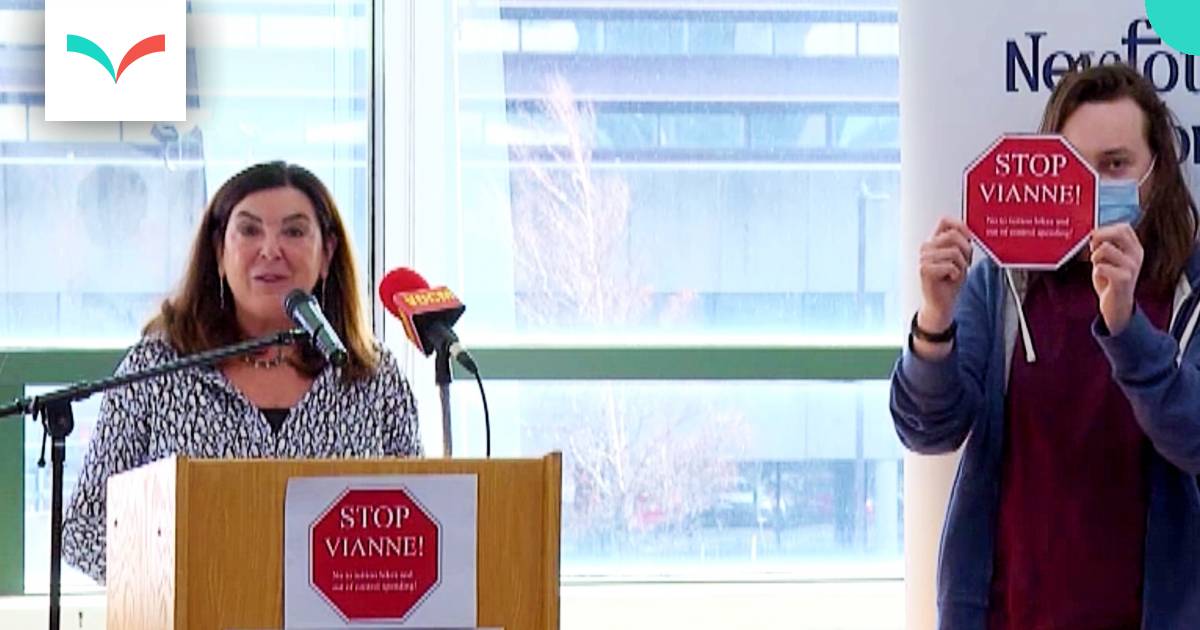

An external investigation into undergraduate student Matthew Barter’s conduct during a demonstration the activist held in December recently found that he violated Memorial’s student code of conduct when he silently protested President Vianne Timmons’s leadership during a government announcement in St. John’s.

Three Memorial University employees, including Timmons, say the 25-year-old political science major crossed a line between protest and harassment. Barter’s partial ban from campus in December sparked a debate around the limits of free expression in the student community.

“No university should be attempting to restrict basic expressive freedom rights that citizens have in Canada, and students shouldn’t have to hire a lawyer and go to court to have their expressive freedom rights upheld.”

In her investigation report, reviewed by Ricochet, St. John’s–based lawyer Kim Horwood says Barter’s actions during his December 2 protest “constitute bullying or harassment” and “disruption” in violation of Memorial’s student code of conduct, but that it’s ultimately unclear whether the rules have been fairly applied to him in the absence of precedent.

Horwood recommends that Barter be directed to “refrain from personal attacks in his protests in the future,” and be prohibited from “protesting inside any class, meeting, or event.”

Barter and his lawyer Kyle Rees have maintained that the interim sanctions restricting Barter’s participation in campus life, and the investigation, represent an attempt by the university administration to silence one of its staunchest critics. They say the case could set a dangerous precedent for the university’s student community.

Following the cessation of campus newspaper The Muse’s print edition in 2017, Barter has partially filled a gap in local news by regularly reporting on Memorial University administrative and financial matters via his blog. An accessible education activist, he has also organized protest campaigns criticizing university leadership’s fiscal policies, including its oversight of unprecedented tuition fee increases.

“The recommendations made by the investigator have dire implications to the entire student body, specifically what locations are acceptable for protest,” Barter wrote in a March 5 post to his blog, in which he also published the investigation report’s conclusion. “Students have the right to protest without fear of repercussions from Memorial University’s top brass.”

CCLA Director of Fundamental Freedoms Cara Zwibel says the university’s interim sanctions against Barter have been “extreme” and that there’s a “decent argument” Memorial has violated his Charter rights.

Jim Turk, director of Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Free Expression, told Ricochet that “no university should be attempting to restrict basic expressive freedom rights that citizens have in Canada, and students shouldn’t have to hire a lawyer and go to court to have their expressive freedom rights upheld.”

After reviewing the investigator’s report, Turk says “the whole thing is loaded against him in ways that are inappropriate,” and that Memorial’s treatment of Barter could deter students from participating in protest at a formative time and place in their lives for political and civic engagement.

Turk and Zwibel both say universities’ weaponization of student conduct policies to silence dissent represents a serious attack on free expression.

On December 2 Barter attended a joint announcement by the province and university for $120,000 in support for international student graduates. When Timmons addressed the crowd, Barter affixed a roughly 8-inch mock stop sign poster that read “Stop Vianne” and “no to tuition hikes and out of control spending” to the front of the podium. Wearing a non-medical safety mask, Barter then stood a few feet to Timmons’ left while silently holding up an identical sign.

The following day, he was banned from campus except to attend classes and was required to report to campus security.

On December 7, Barter received a letter from Jennifer Browne, Memorial’s director of student life, alleging he had breached two sections of Memorial’s student code of conduct: one that prohibits “bullying, intimidating, or harassing another person,” and another prohibiting “disruption” of an activity or of an individual’s rights “to carry on their legitimate activities, to speak to or associate with others.”

Browne’s letter, sent five days after Barter’s protest, did not specify how the university felt Barter had violated the policy.

Barter has maintained that his right to protest is protected under Memorial’s code of conduct, which states that “silent or symbolic protest” is not considered a “disruption” under the code, and that “peaceful assemblies, demonstrations, picketing or other activity outside a class or meeting that does not substantially interfere with the communication inside, or impede access to the meeting or class” are also acceptable.

The following day, December 8, Barter received a letter from the complainant, Memorial Chief Risk Officer Greg McDougall, who was not physically present at Barter’s protest. The letter references “alleged ‘past patterns of behaviour’, ‘an escalation of reported incidents … which began in 2018’, and an alleged ‘20 incident reports’ in the Memorial Incident Management System,” according to a December 15 letter from Rees to Browne published on Barter’s blog.

Rees tells Browne the university previously took no action against Barter in relation to his activism “presumably because the University recognized that his actions were entirely in keeping with the principles of the Code.

“It is morally unjust and procedurally unfair to use supposed internally-documented incidents, of which Mr. Barter was neither informed nor provided an opportunity to respond to, to justify such a severe sanction as the removal from campus,” Rees writes.

During the investigation Timmons testified that she believes there are around 800 pages of social media posts belonging to Barter and involving her.

“Why are they regularly monitoring his social media accounts?” Rees asks in his letter to Browne. “In Mr. Barter’s view, the University has been attempting to build a case against him, and took advantage of his protest and an opportunity to silence him.”

“The way that the administration tried to present me is as being somebody who’s dangerous and unhinged. But if you look at the video I was just standing there and didn’t say anything.”

According to the investigation report, McDougall said in his written complaint that Barter “waited for a female member of the University leadership team to move to the podium,” and then “proceeded to jump in front of her which resulted in him being in extremely close proximity to her.

“No one had any idea what he was going to do,” McDougall continues, describing how Barter taped his protest sign to the podium and then stood to the side “at a distance of only 3-5 feet” from Timmons. “The behaviour of jumping up in front of her was alarming, and together with remaining in close proximity to her while she spoke, was a form of intimidation and harassment.”

In his response to the report, Rees calls McDougall’s characterization of Barter’s actions a “dramatic recounting of the event [that] is not borne out by the video evidence.”

Video from an NTV story on Memorial’s response to the protest shows Barter affixing his sign to the podium over the course of about three seconds, and then stepping aside to hold up his sign. Barter holds the piece of paper in front of his face and doesn’t appear to gesture or even look at Timmons while she is speaking.

Barter says “there’s an element of discrimination” in the way he is characterized in the report. “The way that the administration tried to present me is as being somebody who’s dangerous and unhinged,” he says. “But if you look at the video I was just standing there and didn’t say anything.”

According to the report, Timmons claims Barter emailed her while she was still working at the University of Regina before she began her tenure at Memorial in March 2020. The report does not indicate how many emails Timmons received, or their content. Barter told Ricochet he sent exactly five emails, and that the president-designate responded to his concern around an admissions policy that Barter says discriminates against students with disabilities and thanked him for bringing the matter to her attention.

Barter then publicly thanked Timmons in a letter to the editor published in The Telegram.

Two years later, in her testimony to Horwood, Timmons describes Barter’s poster and social media campaigns as “relentless,” arguing that since Barter had printed her face on posters that were posted on and off campus, his protests against her leadership “became very personal.”

In September Barter protested the university’s decision to more than double tuition fees for new students from Newfoundland and Labrador, and to nearly double fees for out-of-province students. He put up posters around campus featuring a photo of Timmons along with the words “resign” and “no to tuition hikes!”

Timmons ordered the posters removed, citing Memorial’s respectful workplace policy. She told CBC she was concerned about the personal nature of the posters, and that she “wanted to make a statement that this was an important place where everyone needed to feel welcome and part of our community.”

Some in the university community criticized the move, including Memorial’s faculty association. “The posters calling for your resignation do not constitute harassment, particularly in a university context,” association president Josh Lepawsky wrote in an October letter to Timmons. “Rather than a personal attack, we understand those posters as a form of protest directed at the public role of the university president, rather than you as an individual person.”

Lepawsky said Timmons’ response to Barter’s posters “could have a chilling effect on free expression and Academic Freedom at Memorial University.”

During the investigation, McDougall told Horwood that while the university “has the utmost respect [for] freedom of expression” and “unequivocally supports” everyone’s right to protest, “such protest and freedom of expression must be done in a manner that does not involve intimidating, harassing and stalking behaviour or behaviours that generally make members of the campus community feel unsafe or threatened.”

He said Barter should “respect other individuals’ right to freedom of harassment in their workplace/school and behave in a manner that preserves his right of protest and free speech but does not allow him to target and intimidate individuals with loud, volatile and erratic actions that invade their personal space and their places of work and study.”

Barter’s actions may have been “annoying and irritating, and frustrating for someone in the administration who feels like they’re constantly being criticized. I think that’s sort of what the job is about.”

Zwibel disagrees with McDougall’s and Timmons’ framing of the issue. She says what she sees in the investigator’s report about Barter’s behaviour “doesn’t jump out […] as being intimidating or threatening.”

While Barter’s actions may have been “annoying and irritating, and frustrating for someone in the administration who feels like they’re constantly being criticized,” she says, “I think that’s sort of what the job is about.”

If the university has a case against Barter based on a pattern of behaviour that amounts to harassment, and Barter’s protest was “the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Zwibel adds, “this doesn’t seem like a particularly strong case to me.”

In her analysis, Horwood agrees with McDougall’s claim that silent protest cannot be characterized by an absence of speech alone. The investigator concludes that Barter’s actions “were outside the parameter of what could be contemplated by a silent protest,” and that the protest “was meant to take attention away from the actual event, not merely be silent and symbolic.”

Turk, who reviewed the report, says Barter’s action in December is “exactly” what silent protest is. “Freedom of expression is about the right to express yourself and being able to hear what you want to hear,” he says. “He was expressing himself but he was not preventing the audience from hearing what was going on in any way. So it seems to me that’s precisely within the bounds of what the code of conduct allows.

“Effective protest always makes people feel uncomfortable. It’s when that protest crosses the line and inflicts bodily harm on them or prevents people from speaking or people from hearing that it crosses the line at the university. But he did none of those things.”

But the discomfort felt by one witness to Barter’s protest weighed heavily in Horwood’s findings.

The third and final witness interviewed by Horwood was a Memorial employee who also spoke at the announcement. They told the investigator they were “panicked” and “shocked” when Barter affixed his sign to the podium. The employee “had never been involved in anything like that and couldn’t help but notice how personal the ‘attack’ was,” the report reads. “What was almost more shocking to [them], was that nobody did anything.”

The employee — who did not respond to Ricochet’s request for an interview, but whom we are not naming due to their potential vulnerability as an employee of the university — testified that Barter’s protest was “very personal,” according to the report, and “that it was neither the time, nor the place, for Barter’s particular protest.”

Because they didn’t know who Barter was, the employee “was quite alarmed and had no idea what this stranger might do next,” Horwood writes, describing how the employee, when they took to the podium, “tried to keep it together” during their speech. They “felt Barter’s actions were awful and not only disrespected the president, but the entire event.”

The investigator notes in her report that the “degree of discomfort” the employee felt during Barter’s protest “is an indication that Barter substantially interfered with the purpose of the event,” and as such the protest “constitutes a disruption contrary to the Student Code of Conduct.”

“Effective protest always makes people feel uncomfortable. It’s when that protest crosses the line and inflicts bodily harm on them or prevents people from speaking or people from hearing that it crosses the line at the university. But he did none of those things.”

Responding to Horwood’s report in a March 8 letter to Browne, Rees says the “conclusion that because one participant in the room was uncomfortable with Mr. Barter’s display that the protest was thereby disruptive is incorrect, and would set a precedent whereby any protest can be cause for discipline if one witness feels uneasy during same.”

Barter says that after Horwood interviewed Timmons and McDougall, she indicated to him that she was considering interviewing others on Memorial’s list of potential witnesses. Barter says he told Horwood that if she did interview others, he would appreciate the opportunity to provide her a list of potential witnesses, too.

Rees says others who attended the announcement, including two provincial cabinet ministers, may have offered different views of Barter’s protest.

“The investigator chose to interview select individuals presented by the University, and did not speak with other members of the University community who would offer a different view,” he says in his letter.

Horwood declined an interview request for this story, citing the fact that a decision in the case was still pending.

Rees claims in his March 8 letter that Minister of Immigration, Population Growth and Skills Gerry Byrne “gave Mr. Barter a ‘thumbs up’ during his protest action,” and that after the event Minister of Environment and Climate Change Bernard Davis remarked to Barter that “everyone has the right to stand up for what they believe in.”

“These individuals could have been interviewed, and clearly through their actions endorsed Mr. Barter’s right to protest.”

Ricochet requested comment from Byrne and Davis — who were seated in the front row during Barter’s protest — but did not receive a response from Davis’s office and was told by Byrne’s office that the minister would not comment “as this is a legal matter between the university and a student.”

Rees has asked the university to either dismiss the complaint or assign the investigator to interview student union representatives and the political representatives present at the event before it responds to Horwood’s recommendations.

He has also raised concerns around the characterization of Barter as a “harasser of women,” Rees says in his December letter to Browne, arguing it’s “an attempt to embarrass and silence Mr. Barter, and to discourage him from continuing his criticism of University management.”

According to the report, Timmons testified that she feels Barter’s behaviour “is incessant and specifically targets women,” and that her office staff “have begun locking the office doors at the university out of fear of being personally confronted.” The report does not indicate if Horwood sought any evidence of this.

Recalling the day of Barter’s protest, the president says that after Barter affixed the poster to the podium, he “stood about one foot away” from her, and that while she spoke she noticed that a woman who was slated to speak after her “looked terrified.”

The president says while she supports students’ right to protest, what Barter is doing “is something different,” Horwood writes, and that she’s “fearful of others whom he might incite.” Horwood notes Timmons also said that a “person is harmless until he’s not,” and that “by then it might be too late for action.”

McDougall told Horwood that Barter’s actions “crossed a line” when Barter “slapped something on the podium while Timmons was talking,” and when Barter “violated her personal space, contrary to COVID protocols [and] took a selfie while doing it, the purpose of which could only be to humiliate, intimidate, or try to show domination over, Timmons,” according to the report.

It’s an allegation Turk calls “bullshit,” noting that activists always document their protests. Rees also questioned the credibility of McDougall’s claim, asking in his letter to Browne, “Has there ever been a protest where people did not take pictures? Protests that were not documented? How would we know about political struggle but for those who document same?”

Ricochet requested interviews with McDougall, Timmons, and Browne, but none were granted. Memorial’s communications manager, David Sorensen, said in an email on behalf of the university that “the report is not for public release,” and that “it contains personal information about identifiable individuals and Memorial is bound by legal and ethical frameworks to protect the privacy of all who participated in the process.”

Nowhere in the report does it state that the document is confidential, or that its publication is prohibited.

“Should [Ricochet] breach the privacy of persons whose names and other personal information are contained in that report, those individuals may have individual recourse against [Ricochet],” Sorensen wrote.

According to the university, ”the matter really has nothing to do with Mr. Barter’s right to protest, but rather the behaviour he exhibits toward other people in the university community.”

“Personal attacks, it seems to me, would be saying she’s a terrible mother […] or she’s a violent person — not going after her because she’s the president of the university or because of the policy that the university is pursuing.”

In his response to Horwood’s report, Rees says Barter “specifically asked the investigator if there were any comments made around gender issues and she responded that there were not.” He says Barter therefore didn’t have an opportunity to respond to Timmons’ allegation that he targets women, and that there is evidence of Barter “protesting male leaders in equal measure.”

Turk says he doesn’t see any evidence in the investigation that Barter’s protest represents discrimination against women. “Targeting her, a case of one, is not a way of proving a general implication that he’s some sort of misogynist,” he says.

Moreover, Turk says, Timmons’ allegation that Barter’s protest against her is personal doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Barter has repeatedly criticized the university administration’s fiscal policies, including tuition fee increases, under Timmons’ leadership and also under the leadership of former President Gary Kachanoski.

“Is he ever attacking her except in relation to her role in pushing this policy?” Turk asks. “Personal attacks, it seems to me, would be saying she’s a terrible mother […] or she’s a violent person — not going after her because she’s the president of the university or because of the policy that the university is pursuing.”

Turk disputes Horwood’s conclusion that Barter’s protest “was only conducted for the purpose of tormenting or otherwise harassing Timmons.”

“I take it that if Timmons called for a reduction in student fees, Matt would be praising her,” he says. “I mean, that’s the test. If it’s personal, he’ll attack her no matter what she does. But if he’s attacking her because of her policy position, that ipso facto doesn’t make it a personal attack, I don’t think.”

While Barter’s situation could have serious ramifications for freedom of expression in Newfoundland and Labrador’s post-secondary community, Turk says universities’ creation and use of codes of conduct to silence dissent is a generational battle with flashpoints in other provinces.

Student codes of conduct were introduced to a number of Canadian universities in the early 2000s. At the time, they were criticized by student advocates as an overreach by the university into non-academic discipline.

Student representatives — and often faculty and other staff — argued that universities should only enforce codes pertaining to academic issues since non-academic behaviour was already covered by existing law. Critics argued that codes of conduct presented an extra-judicial mechanism by which an unaccountable body of administrators could impose additional rules that might violate the civil rights of students or staff.

In 2006, the administration at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. tried to amend its non-academic code of conduct as a measure to crack down on students who participated in downtown street parties that had become an unofficial part of annual homecoming events. Additional pressure came from Queen’s benefactors, some of whom threatened to withdraw donations from the university unless action was taken to crack down on the off-campus parties.

At the University of Ottawa, a 2008 proposal to introduce a code of conduct was fiercely resisted. Three thousand students signed a petition against the code, and hundreds attended a protest rally. The resistance prompted the university to walk back its plans — but only for a time. In 2014 the university commissioned a task force that explored the option, and the students’ union resisted once more.

This year the university finally succeeded. In February 2022 the University of Ottawa Senate passed the Student Rights and Responsible Conduct Policy, which explicitly states that the policy “is not to be interpreted to interfere with free expression, the free exchange of ideas and debate in an academic environment and it should not be interpreted to prevent Students from participating in respectful debates, peaceful assemblies and demonstrations, lawful picketing. Also, it should not be interpreted in a way that it would inhibit a Student’s right to express their views freely as set out in University Policy 121 – Statement on Free Expression or to criticize or disagree with the University.”

Tim Gulliver, president of the University of Ottawa Students’ Union, says this time the university presented the code as an effort to protect marginalized students, “to be able to have recourse for situations that they’ve experienced that are discriminatory but don’t rise to the level of harassment.”

In a 2021 interview withThe Fulcrum, a student newspaper at the University of Ottawa, Human Rights Office Director Noel Badiou said the policy “is not meant to capture things that are offensive,” but rather “things that are harmful and hurtful to someone else.”

The students’ union succeeded in winning the removal of several clauses, as well as the establishment of an oversight committee with 50 per cent student representation.

“The key concerns were around stifling student dissent, freedom of expression and the university interpreting deliberately vaguely worded sections of the code to decide to shut down people and protestors that they don’t like,” says Gulliver.

Gulliver is hopeful the concessions and safeguards the union obtained will protect students’ rights, and maybe even serve as a model for other campuses. But cases like Barter’s make him nervous.

“I’m not comfortable with a university administration being the judge and jury of how you’re allowed to protest and what you’re allowed to say on campus,” he said. “I’d rather that be covered by the law. I don’t think we need these kangaroo courts set up within university institutions to enforce that.”

Memorial University’s rich history of student protest includes the 10-day occupation of the Arts & Administration building in 1972 to protest administrative interference in the students’ union, and the weeklong shutdown of the Prince Philip Parkway in 1980 to demand better safety measures after student Judy Lynn Ford was killed crossing the street. Student activism has been a vibrant and defining characteristic of the province’s only university.

Students have occupied government offices, stormed Board of Regents meetings, and marched from one end of the city to the other. An elaborate plan to storm the House of Assembly and disrupt the Throne Speech in 2005 was called off only when Premier Danny Williams conceded to students’ demands to maintain the tuition freeze.

The sanctions proposed in Horwood’s report that would prevent Barter from participating in many of the protests organized by the Memorial University Students’ Union could put a stain on Memorial’s legacy of student protest and political engagement, according to Hilary Hennessey, director of external affairs, communications, and research for the students’ union.

“Matt should be able to protest at these events that we initiate as a member of our students’ union. He is an undergraduate student at this university, and we want him to have the ability to speak out against decisions that impact him,” she says. “And we want him to stand in a group and feel included socially and be able to find peer support from others who are going through the exact same situation and speaking out.”

Hennessey believes the university’s response to Barter’s protest “provokes and instills a lot of fear in students, and probably will prevent them from speaking out in future due to the uncertainty about getting penalized for protesting silently or symbolically.”

Zwibel says a big concern with a university code of conduct “is the risk that it becomes weaponized,” an outcome student advocates in Ontario and British Columbia fear is happening at their institutions.

The university’s response to Barter’s protest “provokes and instills a lot of fear in students, and probably will prevent them from speaking out in future due to the uncertainty about getting penalized for protesting silently or symbolically.”

Last year student conduct policies were used in at least two instances to shut down protests around climate change. In September 2021, ahead of a vote on fossil fuel divestment by Simon Fraser University’s Board of Governors, students at the Burnaby campus painted a washable mural on a campus wall calling for action on climate change. Although the mural was easily washed off, the students were threatened with discipline.

At McMaster University in November 2021, student volunteers with the pro-divestment group MacDivest were stopped by campus security while postering on campus and then banned from the campus except for academic reasons, according to the Canadian Federation of Students’ Ontario chapter.

“The weaponization of student misconduct policies against students who call for divestment from fossil fuels shows blatant disregard for the freedom to protest and demonstrate, and further indicates that universities would rather police students and continue to profit off of fossil fuel investments, than confront their own ethical misconduct as they contribute to the climate crisis,” the Canadian Federation of Students said in a statement of solidarity with student organizers at both universities.

“Students should be free to access campus and to be part of student organizing without fears of being policed by campus security or penalized for their participation in peaceful actions.”

Zwibel says while the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects freedom of expression “in very broad terms,” any form of expression involving violence is treated differently. “Once you start to say this is violence, or this makes me unsafe, there’s just no application here,” she explains.

“And you see elements of that in [Barter’s] case, where it seems that some of the university administration is saying, we’re all for protest but that’s not what this is — it’s something different. And that line between intimidation and when acts are experienced as threatening to people, there’s a really subjective element to it. And I think it’s a problem here.”

Zwibel says that while she isn’t privy to all the information about Barter’s case, “I was surprised this was a hill that the university would choose to die on.

“It may have been experienced by people at the particular event as intimidating or threatening in some ways, but it seems like a relatively low key way of protesting,” she continues. “And certainly there seems to be some suggestion [that] this wasn’t the right time or the right place, and it wasn’t relevant. That’s not really how protest works; the individual or the cause that you’re protesting against doesn’t get to tell you where and when you can make your case.”

Timmons’ allegation that Barter’s protest was of a personal nature calls into question the societal role of universities and those who lead them.

Gulliver says there’s nothing wrong with calling on public figures to resign.

“If the university is saying that calling for the president to resign is harassment or bullying then the university president needs to find a different job. It’s a political environment,” he says, adding Memorial “is a publicly funded institution that students attend, and they should be free to express their points of view as long as it doesn’t constitute discrimination.

“And if the university is using the code to shut down dissent then the university should perhaps think about why people are protesting in the first place and act upon that instead.”

Barter has said publicly he’s willing to take the matter to the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador, partly contingent on how the university responds to the investigation.

If that happens, it wouldn’t be the first time a Canadian university faces a legal challenge to its code of conduct. In 2012, the University of Calgary lost a case against two students who challenged the university’s disciplinary actions against them.

In that case, seven undergraduate students had posted critical comments about a professor in a public Facebook group. The university found all 10 members of the group guilty of non-academic misconduct, even those who had not posted about the subject. Two of the students who posted critical comments, brothers Keith and Steven Pridgen, faced particularly strong sanctions including 24 months’ probation, a letter of apology, and a commitment to refrain from posting or circulating additional material that could “unjustifiably bring the University […] into disrepute.” Failure to abide by these rules, they were warned, could lead to additional measures such as expulsion.

“The test of a student code of conduct, for me, is: is it consistent with the fundamental values reflected in our Charter with regard to freedom of expression? And stopping people from protesting when it’s not violent or not stopping events from happening would be inconsistent with our Charter protections for freedom of assembly, for freedom of expression.”

The Pridgens appealed the case through the university’s own processes, which upheld the decision against them. They appealed to the university’s Board of Governors, which declined to hear the appeal. So they took the university to court. The first judge who heard the case ruled in the students’ favour and quashed the disciplinary actions against them on the basis that the university’s actions were unreasonable and also violated the students’ Charter rights.

When the University of Calgary appealed the decision, an appeals court again ruled in favour of the students. In its judgment, the court stated that disciplinary actions toward students at a university “are not solely private or internal in nature,” and that “[t]he relationship between a university and its students, at least when it comes to misconduct of a non-academic nature, has a public dimension that is missing in purely private situations.

“A public university is neither a private club nor a true private corporation; it does not exist purely for or within itself. Rather it is a place for advanced learning, study, research, dialogue and discussion for the benefit of society as a whole,” Alberta Court of Appeal Justice Marina Paperny wrote in the 2012 decision.

“In exercising its statutory authority to discipline students for non-academic misconduct, it is incumbent on the [university] to interpret and apply the Student Misconduct Policy in light of the students’ Charter rights, including their freedom of expression.”

Barter says that during the investigation he raised concerns about his Charter rights, but that Horwood indicated it was outside the scope of her work.

“There are questions around the extent to which the Charter applies to universities, and whether they’re part of government in this context,” says Zwibel. “I think in this context there’s probably a decent argument that the Charter is directly engaged, but […] certainly there were some procedural fairness issues that came up here, and the fact that he was subjected to some sanctions before there was any investigation.

“If he had come onto campus with a knife or some other egregious act, I could understand that step being taken, but this is not that,” Zwibel continues, adding that Barter’s partial ban from campus and having to submit to surveillance are “fairly extreme sanctions.”

In mid-January, after public outcry and pressure from Rees, Memorial gave Barter access to the library and university centre but maintained other restrictions.

Gulliver says the issue speaks to core questions about what a public university is meant to be.

“It definitely is a pattern with codes of conduct like this, for the university administration to use it to stifle dissent and peaceful political protest. And I think that’s a shame because universities often claim that their professors have academic freedom, that universities should be marketplaces of knowledge and ideas, but then the university is the first to shut down ideas or different ways of expressing oneself that harm the university’s reputation. So what is it? Is the university a business with private policies? Or is it a public service where information and knowledge are shared? You have to pick.”

In her report, Horwood suggests Memorial revisit its code of conduct in light of the problems Barter’s case has raised.

“The test of a student code of conduct, for me, is: is it consistent with the fundamental values reflected in our Charter with regard to freedom of expression?” says Turk. “And stopping people from protesting when it’s not violent or not stopping events from happening would be inconsistent with our Charter protections for freedom of assembly, for freedom of expression.”

Zwibel warns that it’s not just the code itself that needs to be revisited, but the implementation process as well.

“It seems to me that maybe there should be a different process in place when the complainant is a member of the administration. I think I had always thought of these codes of conduct as a way to protect students from other students, but there’s a different power dynamic at play when you have a member of the administration involved.”

She warns that any time the code is invoked, the university is sending a message, and that targeting student protestors could have a “chilling effect” on freedom of expression at universities.

Turk says that “one of the purposes of the university is to help people become more effective, engaged citizens in a democratic society, which means modeling the kind of behaviour and values that we have as a society.

“Our Charter claims one of the fundamental freedoms in Canada is freedom of expression, so you certainly wouldn’t want a university being a model for more repression of freedom of expression than is a general citizen’s right on a street corner in the town in which the university is located.”