What is Canadian feminism?

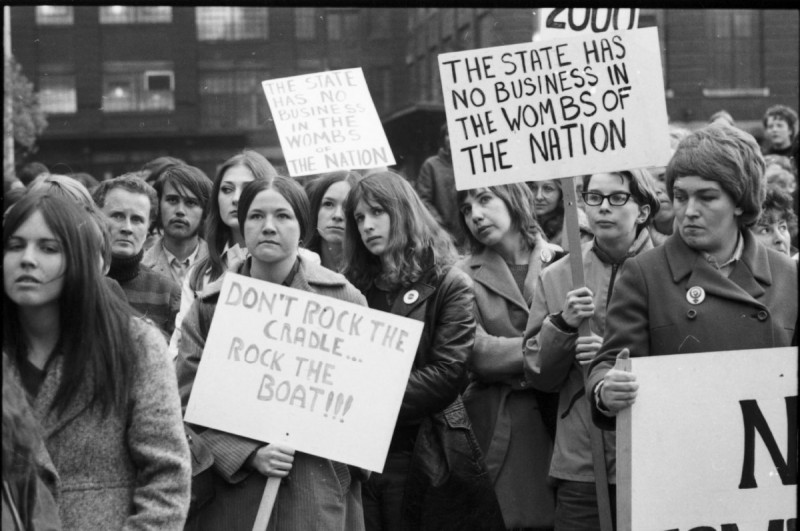

New feminists abortion caravan in Toronto, 1970. Photo by Jac Holland, courtesy the York University Libraries/Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections/Toronto Telegram fonds (F0433).

The following is an excerpt from Demanding Equality: One Hundred Years of Canadian Feminism by historian, professor and author Joan Sangster, released this year by University of British Columbia Press. For more information, visit www.ubcpress.com.

Feminism has been categorized variously as theory, ideas, organizations, movements, sensibilities, feelings, even a way of living. It can be some and all of those. However, if we define it too expansively, it can dissolve into an amorphous description of all women’s empowering political activity. Feminism is more specific: it questions, challenges, and hopes to alter women’s subordination; it encompasses women’s efforts to secure equality, autonomy, and dignity. Can we apply a “feminist” label to women in the past despite their seeming refusal of the term? If we redefine feminism, I think we can.

Feminists understood women to be disadvantaged by their gender, but the origins and experience of disadvantage might be attributed to sexual oppression, patriarchy, class exploitation, racism, colonialism, heterosexism—or combinations of those. Some liberal definitions of feminism stress women’s individual desire to throw of restrictive “encumbrances” as they seek “the self-determination of a freely choosing, autonomous person.” What this definition misses, however, is that autonomy and dignity may be expressed as collective ideals: women from subordinated groups saw women’s emancipation as inseparable from the just treatment of their communities.

Demanding Equality argues that Canadian feminism was polyphonic; it was a chorus of diverse political voices (not necessarily singing in harmony) rather than solos sung by a few women leaders. It is difficult to distinguish a singular feminist consciousness or movement: rather, groups of feminists fashioned different dreams of equality, freedom, and social transformation. Feminism was often a hybrid politics, in which women saw independence, equality, and dignity intertwined with against related injustices, whether racism, war, colonialism, economic inequality, or homophobia.

Certainly, we should not underestimate women’s oppression. It is undeniable that women’s lives from the 1880s to the 1980s not only differed dramatically from men’s but were valued less; women were more constrained than men and regulated and denigrated in ways men were not.

For decades, they could not vote, sit on juries, run for office, have control over their wages, own their own property as married women, secure a divorce on the same terms as men, have custody of their children—the list goes on. Countless laws—such as those delineating self-defence, Indian status, sexual assault—were written in accordance with dominant ideals of patriarchy and masculinity. Social welfare policies similarly encoded gender and racial hierarchies.

All of these political, legal, and social inequalities were qualified and differentiated for women based on their social location: their class, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, place of origin. Because women’s experiences diverged so dramatically, their understanding of feminism and (in)equality differed too. Women of Asian descent could not vote in British Columbia until long after white women secured the franchise; working-class women had fewer economic options and faced more acute economic deprivation than middle-class women; Québec women struggled with intense clerical opposition to equal rights; Indigenous women were subject to the colonial violence of racism and sexism. Indeed, the very meaning of democracy diverged between Indigenous and Eurocentric cultures, and the latter have dominated the history of feminism.

Broadening our definition of feminism, and recognizing that its political, cultural, and social dimensions are entangled, allows us to capture the heterogeneity of feminism and also destabilize the unfortunately tenacious model of feminist waves: the first encompassing suffrage campaigns circa 1900; the second emerging in the 1960s, with more emphasis on sexual liberation; the third taking shape in the 1990s. Despite many historical critiques, the “waves” concept has proven stubbornly popular.

Slotting feminism into waves is problematic not only because it falsely assumes these waves were followed by troughs of inactivity, but also because it obscures the feminist activism of left-wing, labour, ethnic, and racialized women. It also assumes waves are defined and driven by a peer group with a shared political agenda, and fails to acknowledge the ideological differences within feminism in all time periods.

Navigating fragmentary and frustratingly incomplete sources detailing women’s political activities is a perennial concern of feminist historians; every source has its own partialities and challenges, but, pieced together, counterposed to each other, they enable us to reconstruct a more fulsome account of multiple streams of feminist activity. Redefining what is “political” has been essential: rather than tallying up numbers of women successfully running for legislative office, historians have probed local and fleeting mobilizations, unpaid as well as paid work, and efforts to alter the “private” sphere of bodies, families, and relationships. We know that textual and visual records tend to favour the more literate, affluent, English and French speakers, and those with a leadership or public presence.

Feminists were not always cognizant of the historical impact of their activities, they seldom left caches of personal papers, and they were less likely to be sought out by the government, media, or experts for their views. Some were just plain busy, doing the double or triple labour of family care, paid work, and politics, without the time or proclivity to document their political actions and reflections. This was especially so for working-class and racialized women, who often pursued their own pathways to equality, so it is particularly important to locate their equality-seeking efforts. Indigenous women also drew on different cultural practices of historical remembering that were not recorded in our colonial archive. After the 1970s, as a new women’s history emerged, feminists have become far more committed to preserving an archive of their own movement, though much of that current history has yet to be written.

Joan Sangster is Vanier Professor Emeritus at Trent University and a past president of the Canadian Historical Association/Société historique du Canada. She is the author of One Hundred Years of Struggle: The History of Women and the Vote in Canada; Transforming Labour: Women and Work in Postwar Canada; and The Iconic North: Cultural Constructions of Aboriginal Life in Postwar Canada.